Strathclyde People 2017

Professor Mario Stevenson is one of the world’s leading scientific researchers investigating some of the most serious health challenges facing the planet today. He is Chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases with the Miller School of Medicine at the University of Miami, and an internationally respected HIV/AIDS researcher.

But he is also modest, and proud of his background. The 60-year-old Scottish scientist is the son of a steelworker from Airdrie, a former pupil at St Patrick’s High School in Coatbridge, and has a PhD from the University of Strathclyde.

“I love being in Miami for its weather and lifestyle, and it’s where I need to be for my work,” said Professor Stevenson, who described Miami as an ‘epicentre’ for HIV/AIDS infection on an alarming scale – similar to sub-Saharan Africa.

“But I don’t ever forget where I’ve come from; about the day my father took me to the Gartcosh steelworks and I experienced the unbearable heat and noise, and realised it wasn’t going to be for me... or about my time at Strathclyde."

“Would you believe that a project I was working on for my PhD at Strathclyde back in 1984 about cells of the immune system called ‘macrophages’ is playing a big part in my work today on the persistence of viruses within the body?”

“I keep telling my students that in scientific research you need two things: stubbornness and a thick skin – and I have them both in abundance.”

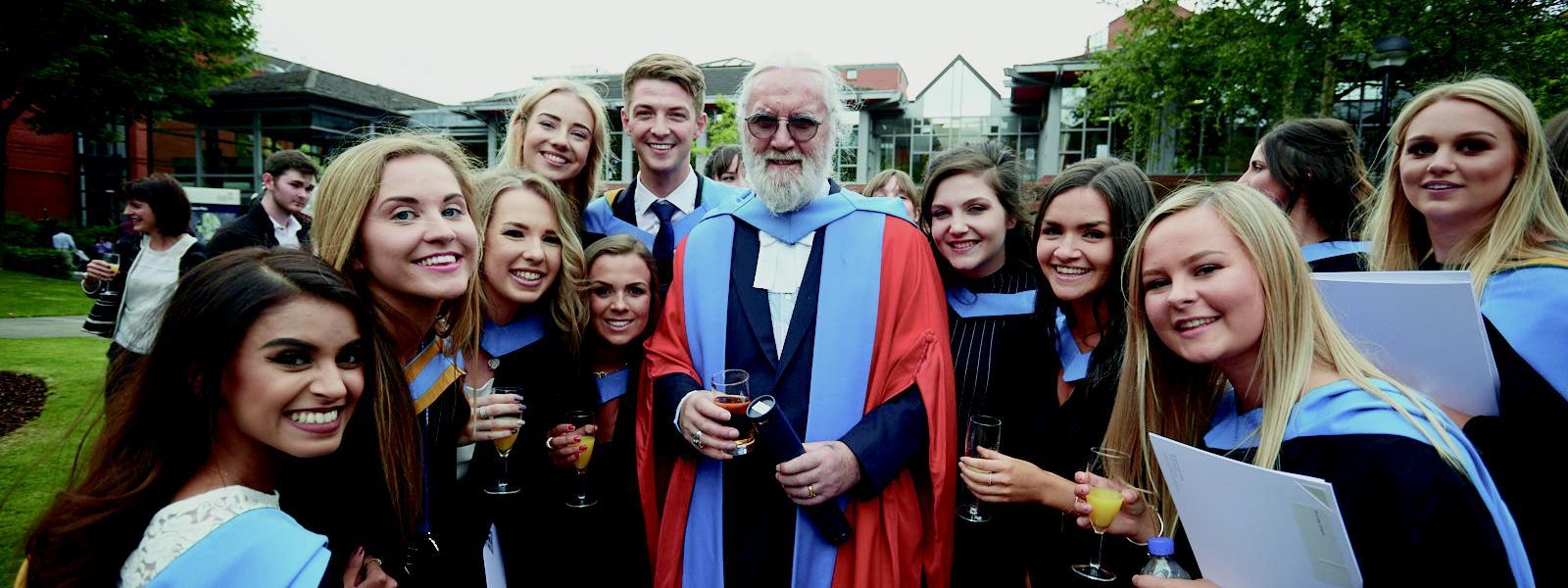

Professor Mario Stevenson

After graduating with his PhD in Pharmaceutical Sciences, Professor Stevenson spent 12 years as Director of the University of Massachusetts’ Center for AIDS Research.

That experience has proven invaluable in the battle against Zika, a mosquito-borne virus that can also be transmitted through unprotected sex. Infection in pregnant women can cause microcephaly – abnormally small heads – and other birth defects.

Zika hit the headlines in the build-up to the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio, when many sportsmen and women pulled out because of fear of infection and the future effects when starting a family. Although cases in Brazil are down this year, and the virus appears to be on the retreat across the Americas, Professor Stevenson urges caution.

“Viruses of this type can take a year or two off because of many reasons,” he explained. “But only around 20% of people who are infected with Zika show symptoms, so the majority of people who are globe-hopping or returning from exotic places just don’t know.

“We need effective testing but, for people planning pregnancy, we also need to understand how long the Zika virus can persist in the body. Only then can we really understand how to eliminate the virus and develop a strategy for a cure.

“The trouble is we know so little. Since AIDS was identified in 1983, there have been more than 300,000 papers published on the subject. That’s a huge body of knowledge. Zika was discovered in 1947 and the first paper was published in 1951. In the 60 years since then, there have been just 2,500 papers – and 1,000 of them have been in the last two years.”

For Professor Stevenson, the challenge of adding to the global body of knowledge is what drives him. He added: “Personally, I’ve always been a naturally curious person, and I think that’s what first got me interested in science at school, and then university.

There’s no better way to spend a day than to come to the lab, and work as a team to try to solve a problem. It’s just so fulfilling.”

More convenient diagnostic tests will make it easier for couples to make informed decisions about whether to try for a child, but can also lead to more effective routine screening of large numbers of the population.

Testing blood samples is expensive and can take weeks to get a result, so Professor Stevenson’s team have developed a test using semen or saliva – at a fraction of the price.

Their work has been boosted by a $13 million grant from the Florida Department of Health to research the disease and help develop a vaccine.

Describing the funding as a ‘big deal’, Professor Stevenson added: “I keep telling my students that in scientific research you need two things: stubbornness and a thick skin – and I have them both in abundance. But whether it’s here or in Strathclyde, you can’t do much without funding.

“Zika isn’t going to be the end of the story. As people travel to more remote regions of the world, we need to be able to respond better to the new threats that will emerge, as well as recent threats like Ebola and Yellow Fever that will undoubtedly re-emerge.”

The Strathclyde Institute of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences is focused on discovering, developing and delivering new and better medicines for the benefit of all. To find out how you can support this research email alumni@strath.ac.uk