This was originally published in June 2010, as part of our Item of the Month series.

With term officially over and thoughts turning to summer holidays, our featured item of the month for June is the travel diary of Miss Mary Pinkerton of Glasgow (1855-1912), niece of the famous private detective, Allan Pinkerton (1819-1884).

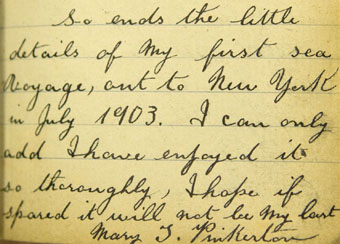

Having completed an apprenticeship as a barrel-maker in the Gorbals area of Glasgow, Allan Pinkerton worked his passage to America in the 1840s, where he settled and discovered a natural talent for investigative work. He established the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, and his two sons, William (1846-1923) and Robert (1848-1907), followed him into the business, inheriting the agency upon his death. Mary Pinkerton’s small, leather-bound notebook (T-PIN/1), which was recently deposited at Strathclyde University Archives by her family, records her first trip from Glasgow to New York in the summer of 1903, where she renewed her acquaintance with her American cousin, Willie, and also met his brother Robert for the first time.

On 11 July 1903, Mary and three travelling companions – Miss Train, Miss Cleland and Mrs Young – left Glasgow on the Allan Line steamer, S.S. Mongolian, waved off by numerous friends who threw pennies onto the vessel for luck. Her diary entries written on board the ship reflect the luxury, romance and unhurried pace of transatlantic travel in the Edwardian era, but also some of the practical problems common to modern-day travellers:

… could any one have peeped into our State room and have seen four ladies dressing in that little Cabin, and heard their remarks where’s my this, and where’s my that, they would have been amused, though it was no laughing [matter] to us. I sleep in a top berth, so I had taken the precaution of tucking my stockings under my pillow, [and] hanging up my Skirt and blouse and the rest at the foot of the bed, which saved me a deal of trouble.

Following an initial bout of seasickness, Mary thoroughly enjoyed her thirteen-day voyage, describing the S.S. Mongolian as ‘a good Ship where you get more food than you are fit to take, and all the officers excell [sic] in Kindness to their passengers.’ Indeed, meals or refreshments were served every two hours according to the schedule Mary noted down:

8 a.m. Breakfast

10 a.m. A cup of beef tea

12 p.m. Dinner

2-3 p.m. Afternoon tea

6 p.m. Tea with fish or meat

8 p.m. Supper

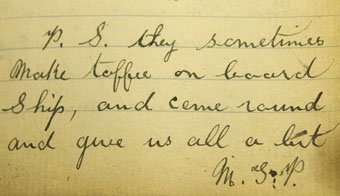

As an extra treat, the officers ‘sometimes make toffee on board Ship, and come round and give us all a bit’!

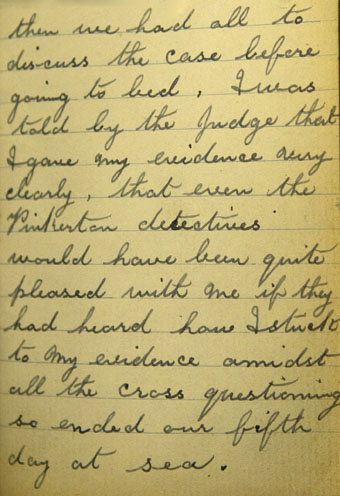

When not at the dining table, she and her fellow passengers whiled away the hours by taking brisk walks along the deck, playing deck billiards, and watching the whales, sharks and porpoises that occasionally swam alongside the ship. More formal entertainments were organized for the evenings, including concerts, a debate, a tug of war competition, and the mock trial of a gentleman for the theft of a silver matchbox, in which the passengers took full part. Miss Train served as a member of the jury, Mrs Young as a witness for the prosecution, and Mary as a witness for the defence. She noted with pride, ‘I was told by the Judge that I gave my evidence very clearly, that even the Pinkerton detectives would have been quite pleased with me if they had heard how I stuck to my evidence amidst all the cross questioning’. Notwithstanding Mary’s performance in the witness box, the ‘accused’ was found guilty and sentenced to three kisses!

Mary’s diary also highlights the distinction between conditions for cabin passengers and for those in steerage class. When shown round the steerage accommodation, for example, she discovered that ‘their quarters … are very comfortable, but not so retired [as ours], and they get the full swing of the boat’. As the S.S. Mongolian approached New York, the Customs officers came on board to ask all the cabin passengers their age, place of origin, destination, the amount of money they were carrying, whether they had anything liable to duty, and to examine their luggage. This last was a perfunctory affair, for Mary and her companions ‘were very fortunate in getting a nice man who would not allow us to turn out our baggage, the only thing he seemed to want of mine to have a look at, was my [sheet] music [and] when he saw it was not new he did not trouble me about it.’ However, she observed that

Steerage passengers are not put through their questions on board ship or [allowed] to land with the Cabin passengers, they are taken to Ellis Island, and are examined there, and put through their questions, and have to shew [sic] what money they have got, if they have not got thirty dollars, they are not allowed to land, but are sent straight back home again, unless they have a friend that will become a guarantee for them, so that they will not become paupers on the Country.

The S.S. Mongolian docked at New York on 23 July 1903. Mary and her party spent the next six weeks enjoying the hospitality of various American friends in Paterson, Weehawken and Schenectady, and doing a great deal of sightseeing. They visited Grant’s Tomb (‘it is very grand, it stands high, we had to go up one hundred and sixty five steps to get to it’) and Jersey City, which Mary likened to ‘the slums of London, the very people seemed different, some of the factories were coming out, and they were thronging up from the ferries, the girls mostly looked sickly … and the men … had not the stalwart healthy appearance of our [Glaswegian] sons of toil’. The ladies also spent one day in Albany, where they toured the splendid Capitol building, and another in Saratoga, where ‘the Hotels are magnificent, I felt as if I was back in Paris and Switzerland, and the people were so gay’. Leaving her three companions behind in Paterson, Mary then accepted an invitation to spend a few days with the Raymond family in Wollaston, Massachusetts. There she enjoyed an outing to Boston, taking in the State house ‘with its most magnificent gold tower’, Bunker Hill, and Keith’s Theatre, which she pronounced

the most beautiful one ever I was in, it surpasses the one I was in in Genoa … the walls were polished marble, with elegant mirrors all along the walls, marble floor with lovely matting, mirrors on the ceiling, when you looked up you saw the people standing on their heads, a large number of exquisite plants in lovely jars and a large number of lovely lights, it was like fairy land.

Another day brought a trip to the beach at Wollaston, where Mary remarked upon the striking contrast between Scottish and American bathing etiquette:

I was quite amused seeing the ladies and gentlemen going in bathing at the same place, they were finely dressed, and had shoes and stockings on their feet and legs, everything so different from home … I could not resist the water myself, but having no dress with me, I was content with a wade in a retired part of the beach.

Mary’s ultimate purpose in journeying to America was to make the acquaintance of her cousin, Robert Pinkerton; but on arriving at his Broadway office on 1 September, she found that Robert had been called away on business, and his brother, Willie, was there to meet her instead. Robert’s son, Allan, who also worked at the Pinkerton Agency, then arranged for one of their employees to take Mary on an all expenses paid sightseeing tour of the city, including the New York Stock Exchange, Macey’s store, a three-hour pleasure boat trip, and an elegant lunch at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. Mary finally had the pleasure of meeting Robert two days later - just a few hours before she sailed home to Glasgow - and confided to her diary,

what a nice man he is, he said he was so delighted to see me [,] kissed me right away, and denied admittance to many of his employees so as he could have a long talk with me.

After sharing reminiscences of Robert’s mother, Joan, Mary presented Robert with a photograph of herself and Joan and a letter that Joan had written to her. In his turn, Robert informed Mary that he and his brother Willie would be paying for her passage home, leaving her touched and mildly embarrassed by such unexpected generosity.

With considerable sorrow at parting from their genial American hosts and friends, Mary and her companions left New York on 3 September, and arrived back in Glasgow 12 days later. She enjoyed the return passage just as much as the outgoing voyage, and had the distinction of being the only passenger on board who perceived that the ship had briefly run aground in the fog at Bowling. In view of this, she congratulated herself on being ‘a bit of a Sailor’!

While the entries describing Mary’s meetings with her two cousins are undoubtedly interesting, it is the wealth of social details contained in the diary that most fascinate the reader. Mary Pinkerton’s journal evokes all the excitement and romance of transatlantic travels in the days when the only way to reach America was by ship, and when fog and icebergs, rather than volcanic ash clouds, were the likeliest hazards for holiday-makers. Yet it is also comforting to note that some of Mary’s holiday experiences – such as a bad case of sunburn on her fair Scottish skin after a sweltering day in Wollaston, and the loss of a bag on the train from Wollaston to Boston (fortunately recovered at the last minute) – remain universal.

Anne Cameron, Archives Assistant