The Nature and Purpose of Practitioner Enquiry

In the second of a two-part series blog, Kate Wall, Anna Beck and Nova Scott explain what is meant by 'practitioner enquiry' and why it is relevant to everyone from student teachers to those with retirement in their sights. The post borrows a section from Kate Wall and Lorna Arnott's new book 'Research Through Play : Participatory Methods in Early Childhood' out in spring 2021.

In our previous post, we explained how a focus on practitioner enquiry has come to underpin the School of Education Professional Graduate Diploma in Education (PGDE) and PGCert in Supporting Teacher Learning. Here we want to explain the nature of practitioner enquiry, and why we see it as such an important approach to professional learning.

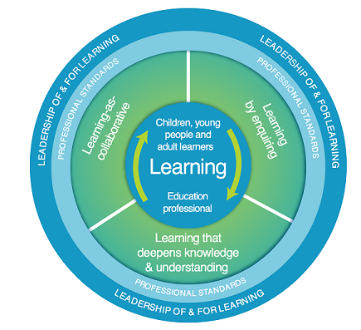

In Scotland, the new National Professional Learning Model (Education Scotland, 2019; see Figure 1) has the concept of research engagement embedded within it including a range of structures and prompts, formal and informal, to facilitate this engagement.

Importantly, at the centre of the model is the relationship between learner and education professional, as such it is emphasising the need to focus professional learning on learner need (Timperley, 2008). For us what it also does is encourages parallels between the learning of children and young people and professional learning, and therefore supports productive connections in the pedagogy used (Wall and Hall, 2016). This thinking is increasingly underpinning work in the School of Education to support students and staff in taking an enquiring approach to their professional learning.

Figure 1: Scottish Professional Learning Model (Education Scotland, 2019)

WHAT IS PRACTITIONER ENQUIRY

In 1916, Dewey first discussed the importance of teachers engaging in pedagogic enquiry to fully understand processes and outcomes in their classrooms. We see two dominant standpoints on practitioner enquiry with a potential lack of transfer between the two resulting in a lack of opportunity for sustainability (Wall 2018). On the one hand we have practitioner enquiry as stance. Originating in the work of researchers such as Cochrane-Smith and Lytle (2009), this position suggests practitioner enquiry is an epistemological stance, a way of understanding the world and how it is made up, arguably a way of being that is tied up with views of democratic purpose and social justice. The other view is practitioner enquiry as project. This is far better publicised, easier to grasp, and as such is probably more dominant in the profession’s consciousness. Here practitioner enquiry tends to be driven by structures and organisations.

Menter et al. (2010) defined enquiry as a strategic finding out, a shared process of investigation that can be explained or defended. This is an orientation much more directly associated with research, via the language of strategic enquiry. Often perceived as more achievable in its boundedness and immediate tangibility, one of the challenges is that each ‘project’ is positioned as separate and finite. While there is nothing to prevent enquiries becoming cumulative and connecting to career long professional learning (Reeves and Drew 2013) this cumulative process is not ‘designed in’: with the focus on the project outcomes, what happens to the enquirer when the module finishes or the organisation moves on?

Within both ‘types’ of practitioner enquiry there is an assumption that the approach will lead to an engagement with research as a means to generate answers to pertinent questions of practice (Nias and Groundwater-Smith, 1988). This could be research-informed and/or involve a research process undertaken by practitioners (Cordingley, 2015, Hall, 2009). Completing a systematic review on the topic, Dagenais et al. (2012) found that practitioners with an inquiry standpoint were more likely to have positive views on research and therefore were more likely to use it to inform their practice. However, beyond those already in the enquiry camp, some practitioners are turned away from practitioner enquiry because of the use of ‘research’: the term itself forming an obstacle. Those practitioners who do not already have an enquiry identity have to perform some kind of translation to achieve a degree of fit with this uncomfortable term.

In our work with practitioners, we have seen forms of translation along a continuum: from ‘importing lab-coats’ and ‘duelling banjos’. In the first, teachers reify research and researchers as ‘other and better’ and import a set of research assumptions, tools and analysis methods wholly inappropriate for the context in which they work. In the second, teachers still consider research as ‘other’ but write it off as alien, irrelevant and in worst cases, threatening to practice. Thus, often with the best of intentions, the ‘project’ can become an add on and the process of enquiry, rather than being a way to find out something useful, becomes meaningless or disconnected from the practice it set out to explore. As is often the case, a meaningful and organic translation sits somewhere between the extremes: chosen by the practitioner, mediated by the research support team.

WHY ENQUIRE?

Practitioners are constantly asking questions which could arise from pressing problems - the learner, stuck and frustrated, right in front of you - or from the growing awareness of a pattern in the classroom - the ‘tried and tested’ has gone stale for learners and teacher alike. Problem solving and exploratory questions - the how can I fix this? and the what’s going on? – are part of the teacher’s innate enquiry process. Our belief is that practitioners are like Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz, she had everything she wanted already and the tools and potential to make the everyday an adventure. Practitioner enquiry therefore has the potential to turn ‘research work’ into an ‘absorbing game’ (Lawrence, 1929).

It is important to recognise that practitioner enquiry is one of many lenses offered under the umbrella of social science research (Hall and Wall 2019). Its strength, and also its challenge, is the close connection between practice and research as the practitioner-researcher takes an embedded and influential position integral to what is under investigation. This means scientific models of research are difficult, if not impossible, to implement. The scientist in a white lab coat having minimal impact on the context and process under investigation is not easily transferable to the practitioner researcher.

Rather than lament this lack of detachment, however, we should embrace the strengths of practitioner-researcher positioning: the unique insight, the access to perspectives, evidence and experience that might otherwise not be considered and the closeness to action in regards iterative development and understanding. We need to value and privilege our knowledge of the pedagogic process, of the context and the children and young people in our care, to value our ‘insider’ knowledge as fundamental to a practitioner enquiry approach.

We need, therefore, to think about the different purposes for which practitioner enquiry might be applied and how different understandings of research might be used and we hope that by linking to the idea of play, in regards the dominant pedagogy of the phase and in regards the nature of professional learning recommended, we encourage a productive synergy for both.

Practitioners can build a bridge that starts in pedagogy and connects to methodology (Wall 2018): an opportunity to merge skill sets. Rather than seeing research as something additional, it can be something useful, integral and indeed, essential, in our teacher repertoire to address the needs of our children. A refocus is needed on what research is trying to do when undertaken by a teacher to explore their practice. If the intent is inherently pedagogical then tools and processes should be evaluated against what is pedagogically appropriate in that setting. Are we trying to measure, to scaffold learning, to change perspectives, to generate new ways to interact? Which tool or which way of using a tool will best support this?

BRIDGING RESEARCH AND PEDAGOGY

When researching real life, we have to accept complexity. It is not possible to transfer a teacher and class into a research laboratory to create experimental conditions: even if we could, this would not iron out the complexities of what each individual brings into the lab from their previous experiences. With each starting point there is likely to be a range of possible factors which might be explored and a number of measures that could be used. The place that any enquiry starts from can only be a best guess: there are always unexpected and unknown factors which impact on the situation we are exploring.

This means that the enquirer needs to work through a number of choices in deciding on the most appropriate question for their study. These choices depend on what makes most sense (to the individual researcher and to the context), what is practical within the organisation (some changes might be impossible to measure, some voices might need creative approaches to be heard and some data might be overwhelming to collect) and who the audience is for the research (will your audience be more convinced by stories, graphs or a combination of the two?).

There is no right or wrong pathway through this process, but you must be clear about the decisions that you have made and why. A colleague reading our work needs to understand the link we’ve made between the outcome and the measure, so we need to present our thinking in a transparent way, acknowledging the variables that might be an influence.

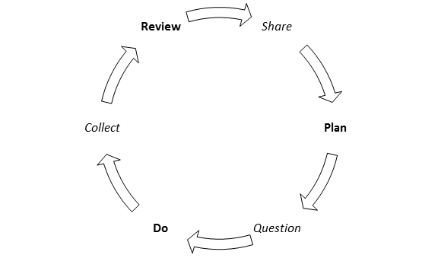

Practitioner enquiry becomes more realistic when we see the productive connections it has with normal practice (Wall and Hall 2017); when it is not something else to fit onto the long list of things to do and the outcomes feel useful in helping to progress practice. Fundamentally we see the enquiry cycle as having good fit onto the plan-do-review cycle that is core to how we teach, how we implement our practice (Baumfield et al. 2012: Figure 2). In this way we are fulfilling Stenhouse’s (1981) blueprint of ‘systematic enquiry made public’ (Stenhouse 1983).

We are not recommending research on every lesson or all the time. Indeed one of the critiques we would level at the project stance on practitioner enquiry approach is that is seems to imply an on/off model of enquiry; rather it would seem more pragmatic to think about a dialling up and down of the research element depending on the motivation of the enquirer and the qualities required of an answer to any particular enquiry question.

Figure 2: Practitioner enquiry as building on the process of plan-do-review

To ensure this model of ‘turning up and down’ the research dial within practitioner enquiry is manageable it needs to be flexible depending on the nature of the enquiry question, and the answer required, as well as to the context in which it is being undertaken and the personal epistemologies of the person undertaking the enquiry (what evidence convinces you?). Therefore, it is helpful to look for bridges and associations.

This is difficult in a system dominated by the language of evaluation, measurement and intervention as promoted in the GERM agenda (for example, Sahlberg 2016). The move towards standardized testing and the 'what works' agenda (Biesta 2007; Katsipataki and Higgins 2016) in many systems around the world means that the common discourse of research most practitioners are familiar with is not sensible or even possible within a practitioner enquiry frame. These are research terms that are more positivist in their epistemology, and as such imply a position of distance between the researcher and the researched to avoid bias, increase reliability and encourage generalisability.

If you are researching your own practice, then you are immersed in the context and integral to the very thing that you are exploring, to try and be true to a viewpoint that fundamentally requires something alternative leads to an unsatisfying and uneasy marriage.

Rather we would suggest a position that recognises the usefulness of the meta-analyses of for example, Hattie (2008), the Education Endowment Foundation (Higgins et al. 2016) and the positivist tradition in education (Morrison 2001; Spybrook et al. 2016), but politely suggests that practitioner enquiry is about doing something different, but complementary, to this.

Practitioner enquiry is not about undertaking large scale experiments to explore high-level trends in education, but rather it is about exploring these ideas in detail, in the real-life context of practice. We believe that when you have a systematic review saying, for example, that self-regulation and metacognition have a range of effect sizes from 0.44 to 0.71 (Higgins et al. 2016), then it is a good bet to focus on in your practitioner enquiry. However, the extent to which it works in your context will depend on multiple things worthy of examination in detail.

It is only when the lenses provided by different types of research are taken together then the two perspectives provide a more convincing and useful way forwards (Thomas, 2016).

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Lorna Arnott and Sage for giving us the go ahead to include a section from ‘Research Through Play: Participatory Methods in Early Childhood’ (details available in full reference below).

Would you like to engage more with practitioner enquiry? Throughout early 2021, the School of Education are running a series of CLPL sessions to support interested colleagues throughout the education system. For details and dates of these sessions, click here (ADD LINK TO CLPL)

References

Arnott, L. and Wall, K. (Eds.) (2021) Research Through Play: Participatory Methods in Early Childhood. Sage.

Baumfield, V., Hall, E. and Wall, K. (2012) Action Research in the Education: Learning through Practitioner Enquiry (2nd Edition). London: Sage

BERA-RSA. (2014). Research and the teaching profession: Building the capacity for a self-improving education system. London: BERA.

Biesta, G. (2007). Why “what works” won’t work: Evidence‐based practice and the democratic deficit in educational research. Educational theory, 57(1), 1-22.

Cochrane-Smith, M. and Lytle, S.L. (2009) Inquiry as Stance: Practitioner Research for the Next Generation, London: Teachers College Press

Cordingley, P. (2015). The contribution of research to teachers’ professional learning and development. Oxford Review of Education, 41(2), 234-252.

Craword-Garret, K., Anderson, S., Grayson, A., & Suter, C. (2015). Transformational practice: critical teacher research in pre-service teacher education, Education Action Research, 23(4), 479-496.

Dagenais, C., Lysenko, L., Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Ramde, J., & Janosz, M. (2012). Use of research-based information by school practitioners and determinants of use: a review of empirical research. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 8(3), 285-309.

Dewey, J. (1916) Democracy and Education Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University

Dewey, J. (1938/1991) Logic, The Theory of Enquiry Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Education Scotland (2018) The National Model for Professional Learning, Education Scotland. Available at: https://www.scelframework.com/about/the-model-of-professional-learning/

Hall, E. (2009) Engaging in and engaging with research: teacher inquiry and development Teachers and teaching: theory and practice, 15, 6, 669-682

Hall, E. and Wall, K. (2019) Research Methods for Understanding Professional Learning, Bloosbury

Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Higgins, S., Katsipataki, M., Villanueva-Aguilera, A.B., Coleman, R., Henderson, P., Major, L.E., Coe, R. & Mason, D. (2016). The Sutton Trust-Education Endowment Foundation Teaching and Learning Toolkit. London, Education Endowment Foundation

Katsipataki, M., & Higgins, S. (2016). What works or what's worked? Evidence from education in the United Kingdom. Procedia, social and behavioral sciences., 217, 903-909.

Lawrence. D.H., (1929) Pansies (450 in the Complete Works)

Menter, I., Elliott, D., Hulme, M. and Lewin, J. (2010) Literature review on teacher education in the twenty-first century, Edinburgh: The Scottish Government

Morrison, K. (2001). Randomised controlled trials for evidence-based education: some problems in judging 'what works'. Evaluation & Research in Education, 15(2), 69-83

Nias, J. and Groundwater-Smith, S. (eds.) (1988) The Enquiring Teacher: supporting and sustaining teacher research. London: Routledge

Reeves, J. and Drew, V. (2013) A Productive Relationship? Testing the Connections between Professional Learning and Practitioner Research, Scottish Educational Review 45 (2), 36-49

Sahlberg, P. (2016). The global educational reform movement and its impact on schooling. The handbook of global education policy, 128-144.

Spybrook, J., Shi, R., & Kelcey, B. (2016). Progress in the past decade: an examination of the precision of cluster randomized trials funded by the US Institute of Education Sciences. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 39(3), 255-267.

Stenhouse, L. (1983). “Research as a basis for teaching. Inaugural lecture from University of East Anglia”. In Authority, education and emancipation, Edited by: Stenhouse, L. 178 London: Heinemann.

Timperley, H.S. (2008) Teacher Professional Learning and Development, Geneva: The international Bureau of Education

Wall, K. (2018) Think Piece: practitioner enquiry, Scotland: GTCS

Wall, K. and Hall, E. (2016) Teachers as Metacognitive Role Models, European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(4): 403-418

Wall, K. and Hall, E. (2017) The teacher in teacher-practitioner research: three principles of inquiry. In Boyd, P. and Szplit, A., International Perspectives: Teachers and Teacher Educators Learning Through Enquiry, Kielce-Krakow: 35-62

Published 12/02/2021

Image - Pixabay