Remembering 90% of What You Do?

In the latest of our posts on misconceptions about learning, Jonathan Firth explains why you can forget the ‘learning pyramid’ edu-myth.

People often hold flawed or inaccurate ideas about how learning works. These can be spread through advice given to students at any point in their education.

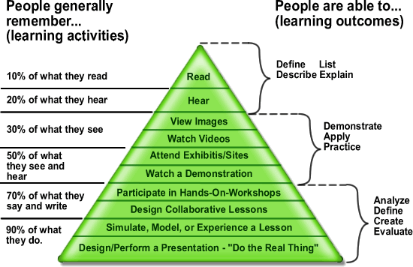

Perhaps you have come across the idea that we remember 10% of what we read, 20% of what we hear, 30% of what we see… etc. These numbers tend to appear in a pyramid-shaped or triangular diagram. You can see a version of it here:

(Credit - Jeffrey Anderson)

This model is often called the learning pyramid (or ‘Dale’s cone of experience’). The upper and lower extremes of the diagram suggest that we will remember only 10% of what we read, 20% of what we hear… but 90% of what we do.

As a memory researcher myself, I’m afraid this just isn’t true. I’ve never come across a properly-controlled experiment which has found one study technique to be nine times as effective as another!

The learning pyramid reconsidered

If the numbers sound like they must have been made up — just a little too exact — that’s because they are. There is no scientific support for this idea/model, and it is not based on research data.

Of course, this doesn’t stop educators and students trying to stick to it. A broad implication is that textbooks and lecture-style teaching should be avoided in favour of active learning. Now, active learning can be effective… but you might wonder how you can do something before you have first read about or been told how to do it!

When you think about it, this aspect of the model really doesn’t make sense.

Getting ‘hands on’ does make sense in some learning situations. If you want to learn to shoot a bow and arrow, for example, it makes more sense to try it out than to read about it.

The trouble is, this doesn’t apply universally. It is actually quite unusual across education.

Consider the following examples:

- Training an engineer to run a nuclear power station. Would you really let them loose to try things out and make a few mistakes without first explaining how things work, or having them read some books about nuclear physics?

- Studying genocide in social studies. Would it really make sense to ‘do the real thing’, as the cone of experience suggests? Or would it perhaps be much more effective (and ethical!) to read about it in a book?

The model just doesn’t stack up. Demonstrations and exhibitions can be helpful, sure, but sadly, students won’t remember 50% of what they experience through these (certainly not after forgetting kicks in), and nor will they retain so very much more from these compared to reading or being taught by a teacher.

In fact, recent research showed that museum visits had no effect at all on students’ exam results.

Boosting exam results, of course, is not really the point of such experiences. No educator would take kids to a museum instead of teaching them. The idea would be to enrich their understanding and experience after they had already learned the basic concepts.

And because of the role of schemas, a student wouldn’t remember as much from a museum visit if they didn’t understand what they were experiencing.

So again, the learning pyramid doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. The sooner we forget this nonsense and focus on evidence-based learning science, the better.

[This post was originally published here].

Explore the Science of Memory in one of our forthcoming CLPL sessions.

Image - Pixabay