This was originally published in May 2011 as part of our Item of the Month series.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928), Scottish architect, designer and artist, was one of the most creative figures of the early twentieth century. His contribution to design and architecture is still internationally recognised, celebrated and respected today. What is, however, perhaps less well known is that a small number of his works are held here at Strathclyde University Archives. These include a pencil sketch of San Michele in Pavia, Italy dating from 1891 (OF 11/7) and a series of seven working plans for the Hill House, Helensburgh, drawn between March 1902 and February 1904 (T-MIN 9/1-7). The latter was commissioned by the Glasgow publisher Walter W. Blackie, a governor of the Glasgow & West of Scotland Technical College, an antecedent of the present University of Strathclyde.

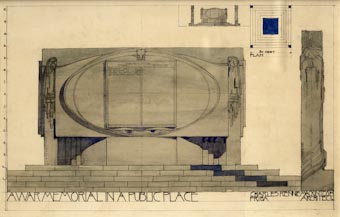

The most strikingly detailed and visually impressive Mackintosh items are, however, housed within our largest non-institutional collection: the Papers of Sir Patrick Geddes (T-GED). These comprise three elevation drawings and plans for a memorial fountain in a public place, a war memorial in a public place and street lamp standards (T-GED 22/1/1413). Created in water colour, ink and pencil on paper, these charming designs are signed and, although undated, appear to have been produced some time between 1915 and 1918.

In both colouring and style the drawings are reminiscent of Mackintosh’s work of 1916-1917 for the house of toy maker and arts patron W J Bassett-Lowke at 78 Derngate, Northampton. In particular, the stepped recesses of the memorial fountain are redolent of the fire surround in the hall. The weeping female figures on the pillars at the corners of the war memorial, in turn, echo the crying females in the panel ‘The Opera of the Sea’, part of an Arts and Crafts Society Exhibition Voices on the Wood from the same year.1

Incredibly, these wonderful items only resurfaced during the 1980s with the commencement of a cataloguing project of the Geddes papers. The question, however, remains: why do they form part of this collection? Sir Patrick Geddes (1854-1932), was a polymath: a biologist, town planner, sociologist and educationist. A friend of Mackintosh, the two men shared a common interest in the arts, architecture, design and the Celtic revival. Geddes had long been a great admirer of Mackintosh’s own work, commenting,

‘The real artist is he who, like Mackintosh in the Art College of Glasgow (one of the most important buildings in Europe) gets his effects within the sternest acceptances of modern conditions. For here never was concrete more concrete, steel more steely…’ 2

The two families also shared a close friendship as seen in letters sent by Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh to Anna Geddes, during the period 1906-1914. In one, for instance, Margaret writes,

‘I am very glad you like us well enough to ask us to put Alastair [the middle Geddes child] up on Saturday night and we should have been delighted to do it – but alas – we have already promised to put up friends…. I am so sorry – we should have liked to have Alastair so much’. (T-GED 9/2175).

Little, however, is known about the background of the three drawings. Most likely they were commissioned from Mackintosh by Geddes as a project or demonstration work in connection with his town planning surveys in India. These occupied the latter for much of the decade 1914-1924. As illustrated by his Cities and Town Planning Exhibition, Geddes sought to introduce the latest modern conveniences to cities, supported by the highest standards of architecture and urban design. This he argued would both facilitate urban renewal and improve the urban environment for its citizens. These three drawings clearly form part of this ongoing project. According to Volker Welter,

‘Almost certainly all these designs were stimulated by Geddes’ charismatic enthusiasm for the city…. They were objects of beauty and they could stimulate feelings of common life as they rooted mutual memories in the civic realm. By offering space for private contemplation at the memorial fountain and for public ritual at the war memorial they could prompt noble aspirations.’ 3

Contemporaries of Mackintosh and Geddes lamented that the two men did not directly and actively collaborate on large-scale projects during their lifetimes. Fernando Agnoletti, lecturer in Italian at Glasgow University, for instance, commented on 8 June 1910,

‘There are in Scotland only two men of genius… Geddes and Mackintosh. Why do they not combine for the sake of their country’s glory and the world’s beauty? Those whom Mackintosh can teach have no more right to ignore him than those whom Geddes can teach have a right to ignore Geddes.' [T-GED 9/1933A)

These three Mackintosh drawings do, in a very small way, serve to connect the work of two of Scotland’s greatest figures as they sought the betterment of society through the adoption of innovative and exciting urban design at the start of the twentieth century.

Kirsteen Croll, Archives Assistant

1Volker M. Welter, ‘Arcades for Lucknow: Patrick Geddes, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Reconstruction of the City’, in Architectural History, Vol. 42 (1999), pp. 331-332.

2Quoted in Paddy Kitchen, ‘A Most Unsettling Person: An Introduction to the Ideas and Life of Patrick Geddes’ (London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1975), p. 149; no source is given.

3Volker M. Welter, pp. 316 & 328.