This was originally published in September 2010 as part of our Item of the Month series.

This month, we feature the recollections of Minnie Blair, née Craig (1865-1956). Born and brought up in Glasgow, Minnie attended St John’s Church David Street School until she was 18 years old. Her recollections, written down shortly before her death in 1956 and transcribed many years later by Minnie’s granddaughter, focus primarily on her schooldays and offer a fascinating glimpse into the life of the Glasgow schoolchild in the mid-nineteenth century.

At this time, the church was the main provider of education in Scotland, and St John’s Church David Street School – popularly known as David Street School – was run by the parish kirk session. Fees, payable on a weekly or monthly basis, were charged for each child, as the statutory principle of compulsory, free education for all had yet to be established. When Minnie was 13 years old, she signed up to become a ‘pupil-teacher’ at the school. Under this scheme, which was introduced in 1846 to help assuage the shortage of teachers at elementary level, eligible older pupils were contracted to teach those children who were younger than themselves, for a period of 5 years. In return, these pupil-teachers received a small stipend (Minnie recalls earning £5 in her first year and £20 by the fifth year), and a free secondary education – something that most boys and girls could never otherwise afford. At David Street School, the pupil-teachers had their own lessons, which included bible studies, history, geography, composition, drawing and (for the girls) sewing, from the headmaster between 8.15 and 9.15 a.m. each morning, before spending the rest of the day instructing the younger children.

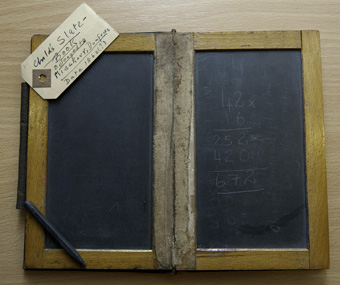

The school consisted of two buildings - one for the infants, and the other for the senior pupils. Minnie describes how the senior school building was divided into three classrooms by means of partitions hauled across the floor and secured with a key; the two end classrooms had coal stoves, but the central room had no heating whatsoever. All three classrooms had gas lighting and were furnished with long desks that seated approximately eight pupils, with a writing slate and an inkwell at each pupil’s place. Amongst their other duties, the male pupil-teachers had to mend the frames of the slates with twine, and they also sharpened the pencils for drawing. Minnie remarks that a box of slate pencils containing four or six stalks cost half a penny when she was at school, but that ‘In the second war I paid 2d for one stalk!’ The photograph below shows a slate with slate pencil held in the University Archives – this example dates from around 1860, and would be very similar to those used by Minnie and her classmates.

Child mill workers, known as ‘dumpers,’ were taught separately from the regular pupils, and received their lessons from two pupil-teachers in the upper room of the infant school building every morning. According to Minnie,

‘They were a rough lot. One day Miss R’s room handle got broken. She did not lock the door but took [the] handle out and kept it in the school room below. On arriving one afternoon to get [her] coat etc. she found they had been removed [,] also [her] hat etc. Where she got suitable garb to go home history does not relate. One of the dumpers had stolen the goods. The room was next door to their room.’

Minnie’s memoir does not reveal how the perpetrators of this transgression were punished, but she implies that the headmaster, Mr Miller, never spared the strap when any regular pupil misbehaved or performed less than satisfactorily in class:

‘One day every week we had to read a paragraph aloud. A boy – Alick [sic] Lochhead – had a very bad stutter. He came to the word hippopotamus. He made several attempts – hippo hippo hippo hippo tamus. The headmaster was furious. He marched about not knowing that his strap which he often put into the back pocket of his coat was gradually falling out. Of course we dare[d] not laugh but felt relieved when it eventually fell on the floor! Reading aloud was a very good part of our education and Mr Miller was very particular about it.’

Fortunately, modern approaches to helping children overcome speech difficulties are both more sensitive and more effective. On another occasion, Minnie and several of her classmates were kept in at lunchtime to do some sums they had failed to master that morning, but Mr Miller - who had taken his lunch break at one of the local pubs - returned earlier than expected to find them jumping and playing among the desks! Minnie recalls that ‘We got severely punished. I went home crying and said I would never go back to that school! An afternoon’s absence put that all right. I did feel sore about the hands.’

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the pupils occasionally enjoyed a little retaliation against the headmaster. Boys would climb onto the rooftops of houses near the school and call out his nickname, ‘Biley Bumps’ (presumably deriving from his poor facial complexion!), when he passed on his way home, until a local policeman intervened to end their fun.

Life at David Street School was not unrelentingly hard work, as the staff sometimes arranged for an elderly gentleman named Mr Dunlop to come and entertain the children. Minnie describes how ‘Mr D. galloped round with a long pointer for a horse and a strap for a whip – great fun for children and perspiration for Mr. D. He left quite satisfied seemingly – and children too seemed pleased.’ Mr Dunlop also told jokes and stories in broad Scots, two examples of which appear in Minnie’s memoir:

‘A little boy fell down stairs one day and his mother hearing his cries ran to help him, saying “Well Johnnie I’m sure your head is broken this time”. “Never mind, Mother” said Johnnie. “You said it was crackit afore.”

A teacher asking class for meaning of word “transparent” was surprised to get [from one boy] the answer “My mother”. He had heard his father say “Guid wife I see through you”!’

In 1872, the Education (Scotland) Act made attendance at primary school compulsory for all children aged between 5 and 13, and introduced new School Boards. Minnie recalls that David Street School saw many improvements as a result of this legislation, acquiring more pupil-teachers and several new, certificated teachers, as well as much-needed classroom equipment in the form of maps and blackboards. Now the pupil-teachers no longer received their lessons from Mr Miller early in the morning, but instead attended special classes four nights a week in the City Public School.

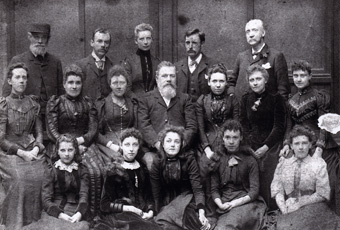

When her five-year contract as a pupil-teacher came to an end, Minnie passed an examination to win a place on a two-year course of teacher training at the Glasgow Free Church Training College (FCTC), antecedent of Jordanhill College of Education. She duly obtained her certificate from the FCTC in 1886 and went on to teach cookery at two different schools in Rothesay, before becoming Infant Mistress at Shields Road School in Glasgow. The photograph above shows the teaching staff of the latter school, with Minnie seated in the second row, third from the left. Shortly after this photograph was taken, Minnie married and resigned from her post at Shields Road. She had a family of six children – virtually a 'private school' of her own. Unfortunately, her recollections do not address that particular period of her life, but they provide an invaluable account of her formative experiences at David Street School.