by Rebecca Zahn - Posted on 30 April 2020

The Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung’s Archive in Bonn, Germany, is a treasure trove for anyone interested in trade union history. I spent a happy fortnight there during my current sabbatical, thanks to a British Academy Small Research Grant, immersed in correspondence and reports drafted by exiled German trade unionists based in London during the Second World War. Even a cursory glance through some of the documentation from that period provides evidence of the strong role that the Trades Union Congress (TUC) played in supporting exiled European trade unionists; a role that has long since been forgotten but which serves as a timely reminder of the importance of solidarity in times of crisis.

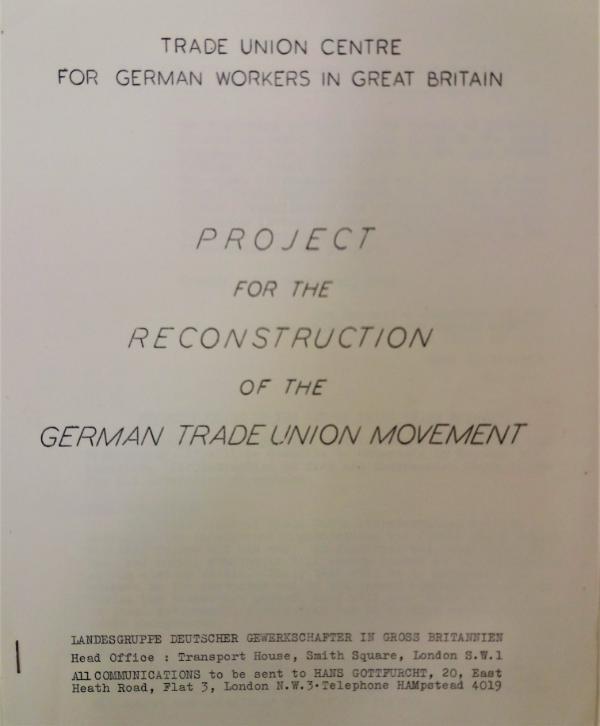

Source: ‘Free Trade Union Movement’, MSS.292/943/22, held in the Trades Union Congress Archive, Modern Records Centre.

I first became interested in exiled German trade unionists when I was researching the origins of German parity codetermination (paritätische Mitbestimmung) – equal worker and management representation on the supervisory boards of certain companies – for an article published in Historical Studies in Industrial Relations in 2015 (those interested can read an abstract). Codetermination was first introduced in the German iron and steel industry by the British military command in 1947. Equal representation on supervisory boards was extended beyond the British military zone in April 1951 by an Act of the German Parliament (Gesetz über die paritätische Mitbestimmung in der Montanindustrie) to cover the coal, and iron and steel industries, and paved the way for the Works Constitution Act 1952 (Betriebsverfassungsgesetz) (amended by the Works Constitution Act 1972) which reintroduced works councils and extended worker representation on supervisory boards to other industries. Employee representatives make up a mandatory one-third of the members of the supervisory board of companies (outside of the coal, iron and steel industries) with more than 500 employees.

In my article, I argued that parity codetermination, rather than a goal in and of itself, was a British compromise and a first step on the road to nationalisation of these industries (which was never completed). I drew parallels – which have largely been overlooked but which help to explain the reasons for the introduction of codetermination – with the debates taking place in the UK with regard to the programme of nationalisation initiated by the new Labour government, elected in July 1945. A question that remained – and which I am now trying to answer – was where the idea for codetermination came from in the first place and to what extent the British had any influence on its design.

Worker participation in the form of some sort of representation in German enterprises has existed in different forms since the 1890s. The concept, as a central tenet of German industrial democracy, has its roots in nineteenth century debates on worker emancipation. However, the term ‘codetermination’ (as opposed to ‘industrial democracy’) only emerged after World War Two and the origins of the particular form of parity codetermination have been traced, by some German scholars, to plans developed by a group of exiled German trade unionists based in the UK during World War Two who combined to form the Trade Union Centre for German Trade Unionists in the UK (Landesgruppe deutscher Gewerkschafter in Grossbritannien). The group has been the subject of research by German historians (mainly as part of bigger projects looking at socialists/political parties in exile) but almost nothing has been written about the Landesgruppe in English.

The Landesgruppe brought together all German trade unionists based in the UK during the Second World War. In 1943, it had approximately 700 members. The majority were based in London but there were also branches in Leeds, Manchester, Glasgow, Birmingham and Llangollen. The Glasgow branch, in particular, appeared to be the most active after that in London. It met 1-2 times per month, organised regular conferences which were attended by local speakers, and had good relationships with British trade unions. It sent a guest delegate to the Trades Council. Its membership (men and women) consisted of miners, technicians, electricians, toolfitters, agricultural workers, typists, and others.

The Landesgruppe’s chairman was Hans Gottfurcht, a German Jewish trade unionist who fled from Germany to the UK in 1938. I have written about Hans Gottfurcht elsewhere. Once in the UK, he and other exiles (men such as Werner Hansen, Walter Auerbach and Willi Eichler but also some women, including Minna Specht) developed comprehensive plans for post-war German reconstruction, volunteered to work for the British government (for example, through re-educating German prisoners of war or recording radio broadcasts for the Allies in German), and tried to influence the British government’s plans for post-war Germany. Some were even recruited by the UK’s Special Operations Executive, trained in Scotland, and sent to Germany as part of ‘Action Goethe’ before the end of the war in order to act as ‘guides’ for the advancing British army.

Letters between Landesgruppe members and British trade unionists, including Walter Citrine (TUC Secretary General) and Ernest Bevin (Minister for Labour (1940-1945) and Foreign Secretary (1945-1951)), before, during and after the war are indicative of close personal and professional relationships. In addition, Gottfurcht regularly attended (and sometimes spoke at) TUC Congresses during the War, and delegates of the TUC were entitled (under the Landesgruppe’s constitution) to attend Landesgruppe meetings. Many German post-war trade union leaders (such as Werner Hansen) were exiled in the UK during the war and had been members of the Landesgruppe.

I would suggest that British influences on codetermination took two forms. On the one hand, Britain provided indirect support by being a place of refuge during the War and enabling a return of the exiles to positions of influence after the War. On the other hand, the close personal and professional relationships between British and exiled German trade unionists also raise the possibility of an active or passive exchange of ideas on worker participation in workplace decision-making during the War.

What is the relevance of this historical material for a labour lawyer? The absence of worker participation in the UK is increasingly bemoaned and has become a topical subject in academic, political and policy debates. Since the 1990s, corporate law scholars have shown resurgent interest in protecting ‘stakeholder rights’ (broadly defined to include workers, consumers and other interest groups) through corporate governance reforms, including providing for worker and other stakeholder representation on company boards. There has been limited engagement by labour law scholars with labour law’s role in providing for worker participation in workplace decision-making. At a political level, Frances O’Grady (the current Secretary General of the TUC) and the Labour and Conservative Parties, including the former Prime Minister, Theresa May, have all called for the appointment of worker representatives to company boards. The nature and form of a British variant of worker participation is disputed however the German model of codetermination is often cited as exemplary. A better understanding of its historic origins and any possible British influences or historic cross-fertilisation of ideas could help the design of a contemporary British system of worker representation based on labour law.