Galaxy clusters caught in the first moment of collision

For the first time, astronomers have found two giant clusters of galaxies that are just about to collide. Since large scale structures in the Universe, like galaxies and clusters of galaxies, are thought to grow by collisions and mergers, this observation can be seen as a missing ‘piece of the puzzle’ in our understanding of the formation of structure in the Universe.

Clusters of galaxies are the largest known bound objects and consist of hundreds of galaxies that each contain hundreds of millions of stars. Since the Big Bang, these objects have been growing by colliding and merging with each other. Due to their large size, with diameters of a few million light years, these collisions can take about a billion years to complete. After this time, the two colliding clusters will have merged into one cluster.

Because the merging process takes much longer than the human life time, we can just see ‘snapshots’ of the various stages of these collisions on the sky. The challenge is to find a couple of clusters that are just in the stage of the collision where they first touch each other. In theory, this stage has a relatively short duration and is therefore hard to find. It is like finding a raindrop that just touches the water surface for the first time in a photograph of a pond during a rain shower. Obviously, such a picture would show a lot of falling droplets and ripples on the water surface that were created after a droplet fell in. Just like in the picture, astronomers found a lot of single clusters and clusters with outgoing ripples indicating a past collision, but, until now, not two clusters that are just about to touch each other.

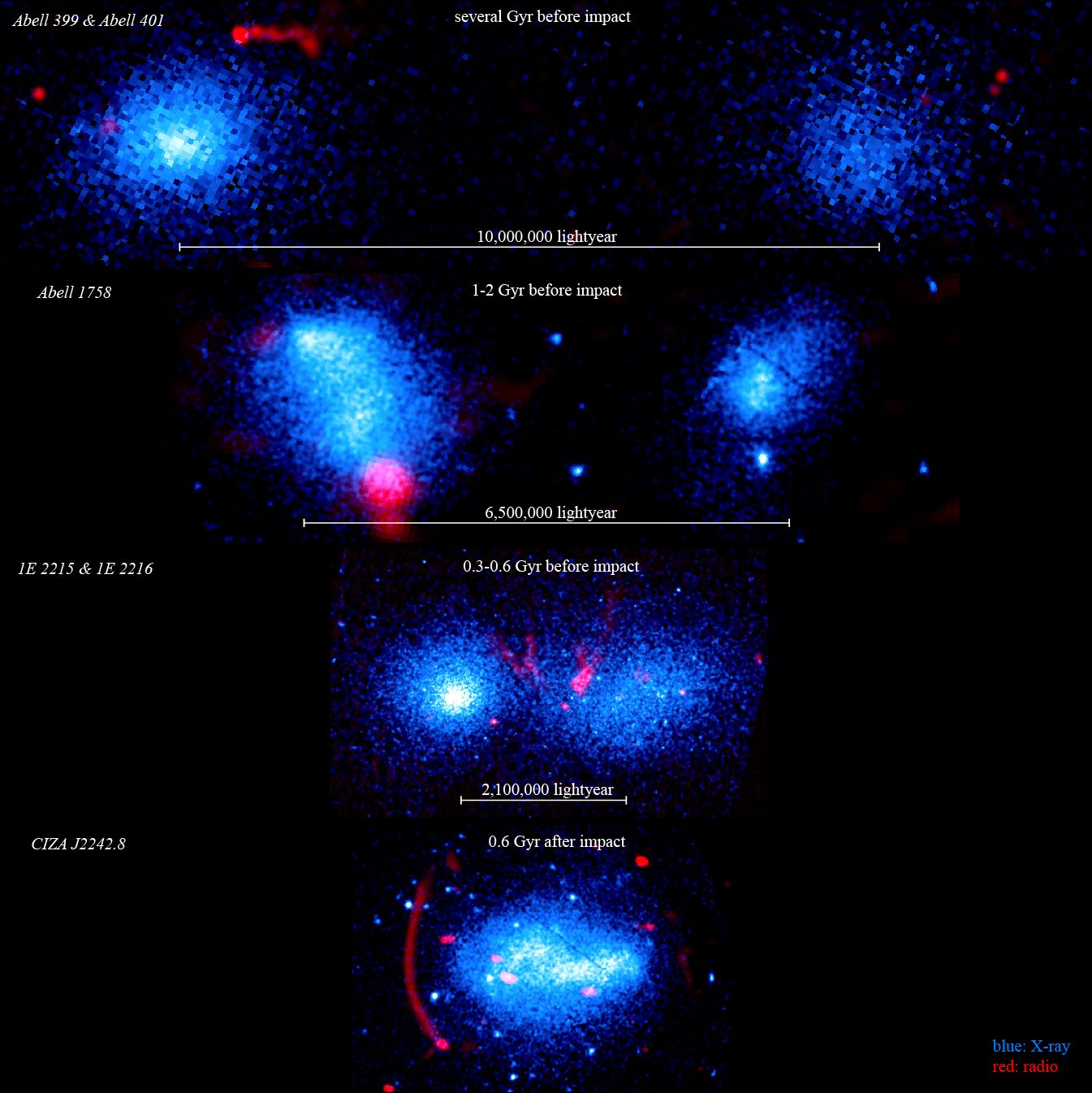

The image illustrates the process of major merger by putting together a set of clusters observed at different merger stages, ordered by the core-to-core distances. X-ray image (blue) is overlaid with the radio image (red) for each object. The third row from the top shows the object reported in the paper. It is rather obvious that this object is seen at the moment of first-touch. The first two rows show objects still far from each other, and the fourth row shows a post-collision object.

An international team of astronomers found the two colliding clusters using multiple X-ray and radio observations. Computer simulations of cluster collisions show that in the first moments a shock wave is created in between the cluster and travels out perpendicular to the merging axis. “These clusters show the first clear evidence for this type of merger shock”, says first author Liyi Gu, a researcher from Japanese institute RIKEN. “The shock created a hot belt region of 100-million-degree gas between the clusters, which is expected to extend up to, or even go beyond the boundary of the giant clusters. Therefore, the observed shock has a huge impact on the evolution of galaxy clusters and large scale structures.”

Astronomers are planning to collect more ‘snapshots’ to ultimately build up a continuous model that describes the evolution of cluster mergers. “More merger clusters like this one will be found by eROSITA, an X-ray all-sky survey mission that will be launched this year,” adds Hiroki Akamatsu, co-author from Dutch institute SRON. “Two other upcoming X-ray missions, XRISM and ATHENA, will allow for a front-seat view of the colossal merger shocks, and help us better understand the role of these shocks in the structure formation history.”

Liyi Gu and his collaborators studied this object during an observation campaign, carried out with three X-ray satellites, including the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton satellite, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Chandra satellite, and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Suzaku satellite, as well as with two radio telescopes, including the Low-Frequency Array (LOFAR), a European project led by the Netherlands, and the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT) operated by the National Centre for Radio Astrophysics of India. The result is published in Nature Astronomy.

June 2019