|

Dr Christian Calvillo 13 September 2018 |

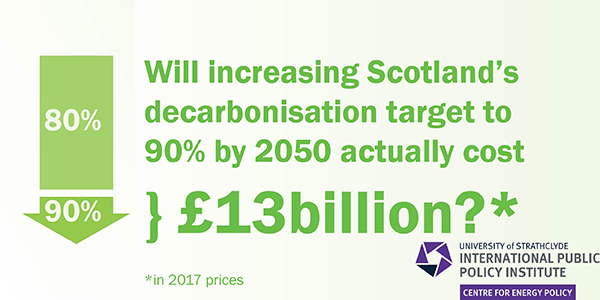

The Climate Change Bill, presented by the Scottish Government in May 2018 seeks to raise the ambition of the 2050 target from an 80% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from the baseline to a 90% reduction. As well as providing the outputs from analysis of the global costs and benefits of climate change action, and the ‘administrative costs’ for the Scottish Government of moving the target, the accompanying Financial Memorandum presents estimates of the whole system costs for Scotland. We have looked at how these calculations were done, and what is included and excluded from them.

The Financial Memorandum briefly explains the process developed, using the Scottish TIMES model, to estimate the whole system cost to achieve the 90% decarbonisation target. It notes that the TIMES-derived analysis considers only total system costs and not any ‘administration’ costs.

Scottish TIMES is a high-level whole energy system model, allowing the analysis of least-cost energy future scenarios (see our earlier report for more information on the TIMES model). Models such as TIMES are particularly useful for conducting whole system analysis, and they can be really effective decision-support tools. However, we have identified a number of issues with the use of technology-driven models, such as TIMES, for assessing costs in the energy system.

Not all the potential costs (and benefits) are considered.

TIMES provides detail in its calculations of technology and energy costs. However, not all costs are considered. Significant omissions include:

- Economy-wide sector and market impacts. Changes to the ways in which sectors exchange (buy and sell) fuel and technologies to one another, have implications on labour, capital and commodity prices, affecting economic growth and energy demand. The analysis developed through TIMES would benefit greatly from also using a whole-economy economic model to understand the impacts on the economy due to the changes in the energy system. See our earlier report for further discussion on this.

- Financial costs. As a model, TIMES assumes that all investment money for the energy system is available. The model does consider an overall discount rate for all investments, but this implies that the cost to borrow money is the same for all sectors and for all projects, which we know is not the case in practice.

- Other social costs and benefits. The decarbonisation of the energy system is likely to bring other costs and benefits to the Scottish people. For instance, improving the energy efficiency of the building stock and the decarbonisation of transport are expected to produce important improvements in health and well-being. These effects cannot be captured in TIMES and other tools and analyses will be needed (as indeed the Scottish Government has recognised; see for example the three ‘Evidence Reviews of the Potential Wider Impacts of Climate Change Mitigation Options’ published by the Scottish Government on 19 January 2017).

The importance of model assumptions.

As a cost-optimising systems model, TIMES is an extremely effective tool for supporting analysis of decarbonisation scenarios. However, its long-term character makes it very sensitive to the assumptions made on demand projections, technology costs profiles and expected technology availability. It is therefore critical that users understand the assumptions made, in order to assess the reliability of the outcomes. Unfortunately, the Financial Memorandum lacked detail on the model assumptions.

We have commented previously on the importance of this in our comments on the Climate Change Plan Technical Annex. We would underline that making model assumptions more transparent would allow closer scrutiny by external stakeholders of the reliability of outputs from the TIMES model.

How can we really know what the energy system will look like in 2050?

To achieve deeper emissions cuts than currently legislated, the energy system will have to change more profoundly than currently projected. The Financial Memorandum recognises that decarbonisation costs increase considerably from 2040 (before that, the energy system under the 80% and 90% targets does not look significantly different), which suggests that the last 10% of decarbonisation is the most difficult to achieve and involves expensive technology changes. The lack of information on the technology mix in 2050 creates two potential problems. i) It may be based on ´future´ technologies that are not widely commercially available yet (e.g. hydrogen or CCS), for which actual costs and performance are likely to be very different from our current expectations. ii) The actual sectoral allocation of costs cannot be assessed, such that we do not know which sectors will have to take on the biggest burden of the decarbonisation target.

Ultimately, who pays and who benefits from this?

At the University of Strathclyde’s Centre for Energy Policy we have two main strands of research relating to climate change policy. Both are critical to developing a deeper understanding of the future whole system costs (and benefits) of the low carbon transition. First, we look at who ultimately ‘pays the bill’ for action to meet policy targets. Second, we consider how a wider range of societal benefits might emerge as a result of taking action(s). These questions are important because climate change policy is particularly subject to ‘public good’ problems where private costs of actions borne by individuals (e.g. energy bill payers) are generally not offset by delivery of private benefits, or at least benefits that are currently valued by those paying the costs.

The problem is compounded by the fact societal benefits do not necessarily accrue where costs are borne. Scottish action to reduce climate change impacts may deliver benefits that ultimately accrue mainly in other parts of the world while costs are borne in a range of ways by Scottish consumers, taxpayers and the wider private and public sectors.

Understanding which parts of society ultimately pay for and benefit from climate actions, and communicating the nature and extent of a wider set of societal costs and benefits arising, provides a solid foundation for developing climate policy that meets wider societal goals of sustainable and inclusive growth. It can help determine both what the overall level of ambition should be (e.g. a 90% or net zero target) and what policy actions should be taken across sectors.

Tags: Energy Blog