The UK Government has now revealed how the £400 Energy Grant Payment will be distributed (in instalments) to all UK households this autumn. The challenge this particular action addresses is soaring energy bills, set in the context of the impacts on natural gas supply in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and a range of supply-chain challenges following the lockdowns of the Covid pandemic.

We use our economy-wide models to simulate the likely impacts of different policy actions and disturbances related to the supply and use of the energy needed to run our homes and businesses. Recently our research has explored how the energy price shock affects the real disposable incomes and spending power of UK households on different incomes. In particular, how the £400 Energy Grant Payment may affect outcomes, particularly for households in the lowest income groups.

The payment is part of the UK Government’s current support for households struggling with the cost-of-living crisis and responded to Ofgem’s Spring 2022 energy price cap increase. In this context, our initial scenario simulations are based on an increase in the price of electricity of just under 32% and a 70% increase in price of gas assuming that it lasts for 2022 and 2023. We’ve also extended our scenario simulations to consider how the picture emerging may be affected where the payments to households will begin just as the price cap rises again.

The macro-economic impact of the energy price shock

Our simulation results show that, for as long as the energy price shock lasts, it causes negative impacts on all major macroeconomic variables, with the knock-on effects of higher energy bills (faced by all producers and consumers) alone accounting for approximately a 0.4% reduction in UK GDP in 2023 and contributing to the recession now predicted by the Bank of England.

Crucially, we estimate that this is associated with the loss of more than 160,000 jobs (measured in terms of full-time equivalents). Employment in service sectors suffers most, due to a combination of the direct impact of energy bills and reduced spending by hard-up households, and because of the labour-intensity of activities such as wholesale and retail trade.

The public budget also takes a serious hit, to the tune of around £9BN per annum for the two years that we’ve assumed the energy price shock lasts. This is due to a combination of lost government revenues as activity falls/the tax base shrinks, and our assumption that some public spending (on transfers and goods/services, though not public sector pay) will be pegged to the Consumer Price Index (CPI) at some point within each year (and this assumption may need to be revisited).

The impact on households from the energy price shock

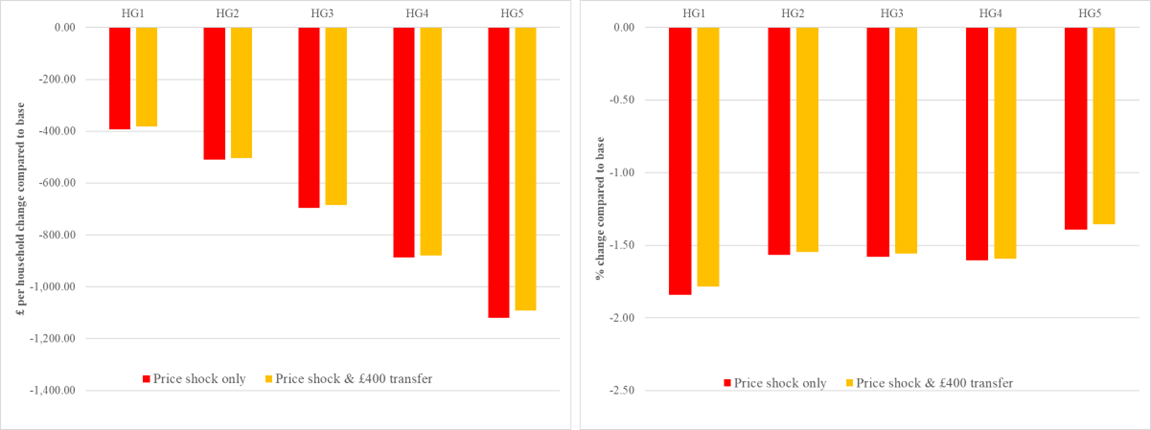

UK households are impacted in a number of ways. The direct impact of higher energy bills is exacerbated by the rising CPI (where the energy price shock alone drives increases of over 1%), which is contained mainly through real wage reductions (averaging around -1.4%). Things will be worse for many households as a result of job losses, as demand for labour falls in different sectors of the economy. In the short term, many households cannot do much to change their behaviour and ways of delivering the heating, transport and other activities they need. Our results show that lower income households suffer the most (see the red bars on the right hand-side Figure 1).

Here, while the absolute value of energy bills and real spending power losses in those 20%-40% of households on the lowest incomes is less than those households on mid-to-high incomes, in percentage terms the impacts are greater. We are assuming that those on benefits will see these rising with the CPI – if this doesn’t happen, the outcomes will be much worse.

Figure 1: Year 1 (2022) changes in average real household income (absolute £ per household and % change) due to 2-year electricity and gas price shock in isolation and combined with a £400 transfer in 2022, for household income quintiles HG1 (lowest 20%) to HG5 (highest 20%)

The impact of the £400 Energy Grant Payment

So, to what extent will the £400 Energy Grant Payment introduced in Autumn 2022 help? Figure 1 shows that the average per household loss across the 20% of households on the lowest incomes (HG1) associated with the energy price shock alone is around this amount in Year 1 (2022). Thus, we would expect the Energy Grant Payment to compensate the average household in this group, this year anyway. Indeed, our results suggest that there could even be a small net income gain for the average household in this group. This is a result of two factors.

First, where the Energy Grant Payment helps partially recover spending across all households, this will cushion the wider economy contraction, and consequent income losses. Second, and crucially, remember that we assume government transfers (e.g. benefits and pensions) are adjusted to compensate for the rising CPI.

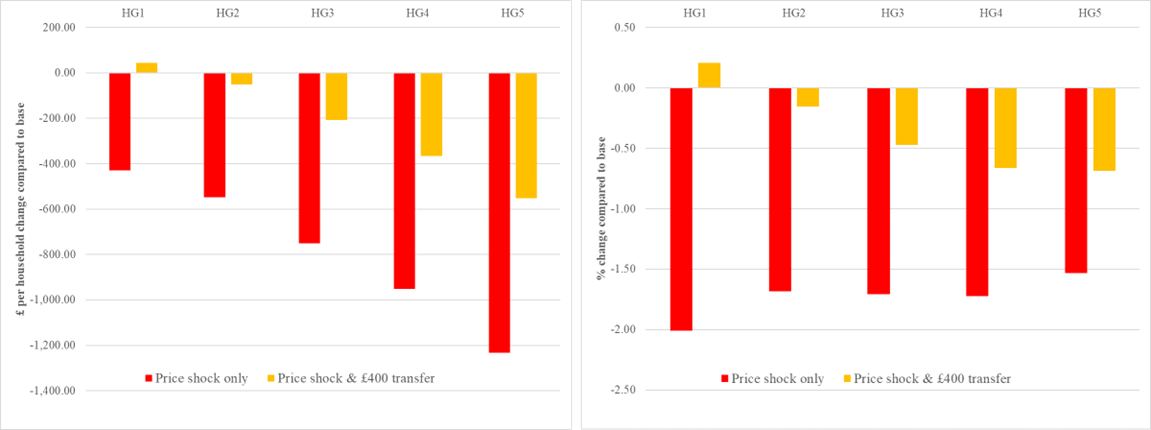

But we have to assume that the price shock will continue into (at least) a second year. The year 2 (2023) results in Figure 2 show that, if no further Energy Grant Payment is forthcoming, the picture reverts to one where all households bear the full brunt of the real income and spending loss of the energy price shock and consequent economy-wide contraction. And, again, if other government transfers do not adjust for the wider CPI increase, the outcomes will be even worse.

Figure 2: Year 2 (2023) changes in average real household income (absolute £ per household and % change) due to 2-year electricity and gas price shock in isolation and combined with a £400 transfer in 2022, for household income quintiles HG1 (lowest 20%) to HG5 (highest 20%)

Understanding the impact of further price increases in October 2022

However, perhaps the most immediate challenge is that the energy price cap is widely projected to rise substantially in October, just around the time that the Energy Grant Payment kicks in. Based on recent Cornwall Insights projections, we estimate that the price shocks we base our simulations need to rise to, at least, 76% for electricity and 206% for gas. When we rerun our simulations with these figures, the wider economy picture becomes substantially worse, with the GDP loss associated with the energy price shock alone rising to 0.96% in 2023, linked to (full-time equivalent) jobs losses in the order of 455,000, and a greater increase in the CPI (2.6%) accompanied by a greater contraction in average real wage rates (-3.4%).

There are some real challenges ahead. With imminent recession predicted, public finances will be further strained by falling revenues and increased nominal spending to ensure that any government transfers (e.g. benefits and pensions) have the same purchasing power.

Here, our results suggest that the wider economy impacts of the energy price shock under the October price cap could increase the public budget deficit by up to £25BN in 2022 and 2023.

The £400 one-off Energy Grant Payment will simply not go far in offsetting real disposable income and spending power losses in all UK households. We estimate that losses to the 20% of UK households on the lowest incomes resulting from the price shock could rise to more than £1,000 in both 2022 and 2023, and that is assuming that the price shock does not (as now predicted by many analysts) continue in 2024.

Ultimately further support, potentially with more targeted and sustained support for those on lower incomes is critical to avoid dramatic increases in fuel and absolute poverty levels.