Ancestral land claims and the law in Namibia

By Willem Odendaal - Posted on 25 June 2020

This is a blog post by Willem Odendaal, a PhD researcher working with our Strathclyde Centre for Environmental Law & Governance (SCELG). A similar version of this article first appeared on 18 June 2020 in a column in The Namibian newspaper.

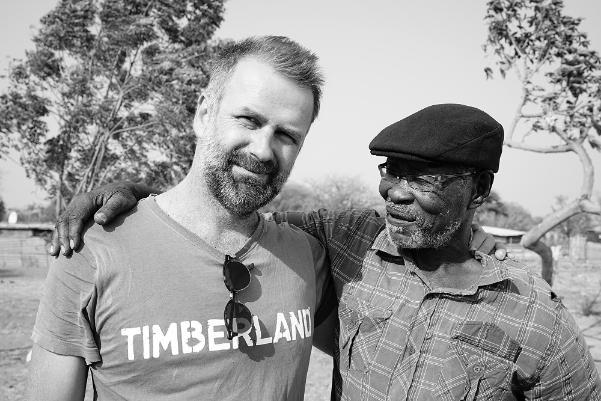

Pictured left to right: Willem Odendaal, the author of this blog post, and Jan Tsumib, a claimant in a Namibian court case about ancestral land.

Many of Namibia’s indigenous communities lost their ancestral lands during the colonial and apartheid times. Yet the topic of ancestral land claims has been an uneasy political debate since Namibia gained its independence in 1990. At the end of the 1991 Land Conference, it was decided that restoring “ancestral lands” would not become part of the Namibian land reform programme. This was motivated by the fear that it might cause various ethnic groups to fight over their rights to ancestral land and as a result, undermine national unity. Consequently, the Namibian policy and legislative framework on land reform has developed in such a way that it does not support ancestral land claims, unlike South Africa, where the Restitution of Land Rights Act was enacted in 1994. The key objective of the 1994 Act is to provide for the restitution of land rights in respect of which persons or communities were dispossessed under or for the purpose of furthering the objects of any racially based discriminatory law during South Africa’s apartheid era.

Despite the Namibian government’s disapproval of ancestral land rights over the years, the debate around ancestral land rights took political centre stage at the Second Land Conference in October 2018 – so much so that President Hage Geingob ordered the establishment of the Commission of Inquiry into the Claims of Ancestral Land Rights and Restitution in February 2019. Its task was to draft a framework for the ancestral land rights question by the end of 2019. However, at the time of writing this article, the outcome of the Commission’s report has not yet been published.

What follows below is a brief discussion of how ancestral land claims could be included in the existing Namibian legislative framework.

Ancestral land claims are not new. The ancestral land rights of indigenous people, and their claims for compensation for the loss of their land, have been recognised in African courts in countries including South Africa, Kenya, Botswana, Australia and Canada. As the Mabo case in Australia has shown, ancestral land claims are mostly relevant in countries that inherited a common law system, as Namibia has, because of the common law rule that “possession” significantly contributes to a claim of ownership.

Given that ancestral land claims have no statutory basis or case precedent in Namibian law, the Namibian Constitution, international law and comparative case law could in principle provide the necessary legal guidance for ancestral land claims in Namibia.

Firstly, Article 12 of the Namibian Constitution provides that anyone is entitled to approach the court to determine his or her rights. This means that when someone is aggrieved by some wrong done to them, they can approach a court to have it remedied.

While the Namibian Constitution does not explicitly recognise the rights of indigenous peoples, it could still provide support to indigenous peoples’ ancestral land claims. For example, Article 10(2) stipulates that no person may be discriminated against on the grounds of sex, race, colour, ethnic origin, religion, creed or social or economic status. Additionally, Article 19 specifies that every person shall be entitled to practice any culture, language, tradition or religion, subject to the terms of the Constitution. Indigenous peoples would seem to fit the criteria of both Articles 10 and 19.

Also, Article 66 of the Namibian Constitution acknowledges the validity of both customary law and common law as long as they are not in conflict with the Constitution or any other statutory law. The application of customary law often plays a central role in ancestral land claim cases. Because of the constitutional recognition of customary law, Namibian Courts have to take notice of customary law when it is appropriate to do so.

Secondly, Namibia is a signatory to several international agreements that are applicable to indigenous peoples, such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP). Article 144 of the Namibian Constitution, affirms that the international agreements to which Namibia is party are automatically incorporated into domestic law.

Thirdly, comparative case law on ancestral land claims, such as the South African Richtersveld case, could have persuasive value in Namibia’s courts. In this case, the Richtersveld community argued that they had occupied and used their ancestral lands as part of their customary rights. Moreover, the South African Constitutional Court ruled that the Richtersveld community’s customary land rights were not extinguished following the invasion of their lands by the colonial government or the present South African State. The Richtersveld case is important, because it recognises an indigenous community’s rights to its lands, based on its customary law.

Similarly, in Namibia, the recognition of customary land rights has been confirmed by the Supreme Court, in the Kashela matter. The key question for decision was: What happens to a person’s unregistered customary land right when the communal land she lived on becomes town council land? The Supreme Court concluded that the customary land right of Ms Kashela had not been extinguished by the proclamation of the Katima Mulilo townlands. Thus, its decision clearly leans towards the rights-giving nature of the Namibian Constitution, reinforced by its declaration that “where there’s a right, there’s a remedy”.

Ancestral land claims have been dismissed by the Namibian government in the past based on the view that such claims are politically undesirable, as well as by the Namibian High Court, which is now the subject of an appeal to the Namibian Supreme Court. The fact that the Commission of Inquiry into the Claims of Ancestral Land Rights and Restitution was established to investigate the desirability (or not) of ancestral land claims in Namibia is a clear response to the call of many of our Namibian communities for inclusion in the present land reform programme. Ancestral land claims, as argued above, are not an unfamiliar concept and have an established foundation in both comparative and international law. Moreover, ancestral land claims also find favour in the legal pluralistic character of the Namibian Constitution. Dismissing ancestral land claims because they raise uneasy political questions should not exclude the possibility that the law, if developed to allow ancestral land claims, could complement and strengthen the existing land reform programme by securing the land rights that so many of Namibia’s minority and marginalised indigenous peoples still do not have.

A similar version of this article first appeared on 18 June 2020 in the Legal Assistance Centre’s Pro Bono column, a weekly feature in The Namibian newspaper. For more on the Legal Assistance Centre please see https://www.lac.org.na/ and for more on The Namibian newspaper please see https://www.namibian.com.na/