Before the dispute: early legal guidance for newcomers in Scotland

By Hamza Rehman (LLM Law, Technology & Innovation, University of Strathclyde) - Posted on 16 December 2025

When I moved to Scotland for my LLM, the legal landscape felt familiar on paper but unfamiliar in practice. I had grown up in Pakistan within a legal tradition shaped by British common law, so I recognised the structures and concepts. What I did not recognise was the lived experience of navigating everyday systems in a new country and how hesitant you can feel about asking for help.

One moment from my first accommodation in Glasgow stays with me. I shared a flat with four other people, two women and two men, living in the same shared space. Over time, it became clear that the two women were being treated poorly by the male flatmates, at times bordering on verbal abuse. When they eventually raised it with me, they were less worried about the behaviour itself than about what might happen if they complained. They were afraid that raising a concern could put their tenancy at risk. They did not realise that Scottish law protects tenants from retaliatory action, or that organisations such as Shelter Scotland or the local council can intervene discreetly on their behalf.

Then came the electric bike story. Another student bought a bike, only for the battery to fail soon after. The seller refused to take responsibility, leaving him frustrated and unsure what to do. We looked together and found Consumer Advice Scotland. One formal letter from them resolved the issue almost instantly. The feeling of relief on his face was unforgettable, he realised how accessible the system truly is once you understand where to turn.

A fellow student once asked me about medication for an allergy. When I suggested he visit a GP, he quietly admitted he had never registered with one. He wasn’t confused by the system; he was intimidated by it, convinced it would be bureaucratic and difficult. Meanwhile, his symptoms were worsening unnecessarily. When I showed him where to start, he registered within minutes. That moment reminded me how easily hesitation can stand between someone and the support they’re fully entitled to.

These were stories of people who had rights but did not yet see how to use the protections already in place. Scotland offers strong, preventive legal frameworks for tenants, patients and consumers, but newcomers often hesitate at the very first step. That hesitation creates a gap between the law on paper and the law in everyday life.

Access to justice is usually imagined as something that begins when a person speaks to a lawyer or appears in court. For newcomers, it often begins much earlier, at the moment when they decide whether to ask a simple question about housing, health or a purchase. Building ScotSpot grew out of that realisation: that early, clear guidance in plain language can prevent many of these issues from ever becoming formal disputes. Justice begins long before any lawyer becomes involved.

When rights are hard to use

The more I listened to these stories, the clearer the pattern became. Scotland already provides a strong set of preventive protections for everyday life. The difficulty lay in something smaller and less visible. Newcomers often did not know how to describe their problem, which public body to approach, or what kind of help was appropriate. Many were unsure whether what they were experiencing even counted as a “legal issue”. A situation that felt uncomfortable or unfair remained a private worry rather than a question for a housing adviser, a medical practitioner or a consumer support service. For someone new to the country, information is only one part of the difficulty. They are also adjusting to a new culture and administrative style while managing study, work or temporary stay. Searching, comparing, and deciding where to begin can feel overwhelming, especially when English is a second language or when someone has never engaged with public services in this way before.

From stories to a design question

ScotSpot began as a simple thought: if newcomers had one place that gathered key Scottish resources in plain language, many of these worries could be eased. My first instinct was to build a static website with archive based guided links, do’s and don'ts, community voices where people share their problems, or the basic folkways or moras related to Scotland's culture from where people can learn and adopt and also websites link of public and private organisations, grouped by topics and categories.

When I discussed this idea with Professor Wes Oliver, he encouraged me to be more precise about what I was trying to change in people’s experience and whether I wanted to do more than simply collect information. His questions shifted the focus from “What can I build?” to “At what point in a newcomer’s journey does guidance matter most, and what should that guidance look like?”

The answer was early, simple direction. They needed something that could recognise an everyday housing, health or consumer concern and gently point them towards the right Scottish service, in words they could act on.

At the same time, I was seeing how more people first turn to conversational tools when they have a legal question. That shift matters for newcomers: the first step is increasingly a guided conversation rather than a search for the right office or phone number.

These two insights shaped a clear design brief for ScotSpot: a first-step conversational tool that gives newcomers early clarity in plain language, connects them with trusted Scottish resources, and stays within a narrow, preventive role rather than acting as a legal adviser.

Building ScotSpot: logic first, technology second

Studying in the LLM Law, Technology & Innovation programme changed how I approached the project. I came to Strathclyde trained to interpret rules. The programme showed me how digital tools can work alongside legal reasoning as part of the same response to a real world problem, and how even basic coding literacy can help break problems into clearer steps.

Before touching any software, I designed ScotSpot on paper. I listed the common situations I was seeing in housing, health and consumer matters, then grouped them into simple categories: deposits and repairs, GP registration and routine care, faulty goods and refunds etc. For each category, I asked three questions: What is the simplest way a newcomer might describe this problem including keywords to detect in the question? Which Scottish service is best placed to help? What is the first action they can realistically take today?

From there, I turned these notes into a branching conversation. Each step needed to do one clear thing: clarify what the user was dealing with, reassure them that help exists, and point them toward a named, trusted Scottish resource. The language had to feel natural to someone who might not know legal terminology, so I avoided doctrine and focused on plain questions and answers.

(Example interactions from the ScotSpot prototype, demonstrating early legal guidance in practice)

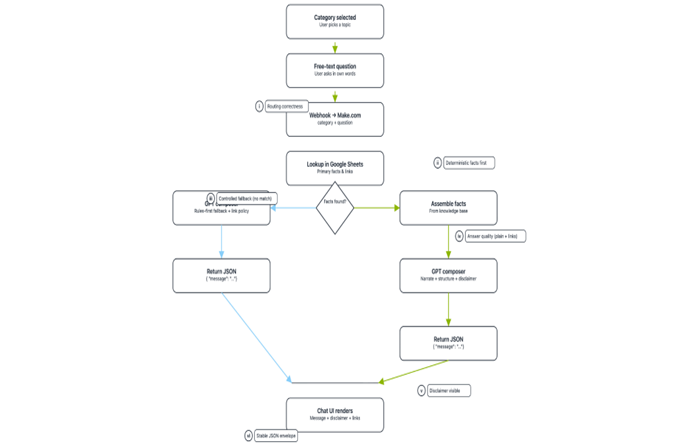

Once the logic started to make sense, I started the implementation. The tool stack was chosen to optimize for quick implementation and rapid prototyping. It consisted of a chat interface, an orchestration layer, simple API integration with LLM and codified rules for answering the questions in a deterministic way, as opposed to the probabilistic response they can get by asking questions directly using tools like chatGPT or gemini etc.

Setting ScotSpot’s boundaries

From the beginning, I had to be clear about what ScotSpot should and should not try to handle. The situations that inspired it were everyday issues, and the tool needed to stay within that space. If it attempted to imitate a lawyer or to interpret detailed facts, it would risk misleading the very people it is meant to help.

ScotSpot is designed as a first step only, not as a legal advisor. It does three things: it listens to a basic description of a problem, it reflects that problem back in clearer, simpler terms, and it points the user to official Scottish sources. It does not give opinions on the strength of a claim, predict outcomes or connect with the legal practitioners.

This boundary is made explicit in the way the tool is presented. The interface explains that ScotSpot offers general guidance and signposting, not legal advice. If a question falls outside the everyday issues the tool was built for, such as a complex immigration status problem or an ongoing court case, the conversation does not continue as if it can answer. Instead, the user is guided to seek direct help from the appropriate organisation.

Thinking about these limits was as important as mapping the categories of issues. It meant translating familiar legal cautions into design decisions: when to hand over to a human, how to avoid a false sense of certainty, and how to keep the focus on trusted public information rather than on the tool’s own voice. Those guardrails make ScotSpot a safe starting point.

What ScotSpot revealed about law, technology and early justice

Working on ScotSpot changed how I think about where law actually meets people’s lives. They were worried about accommodation, health or a purchase that someone felt uneasy about but did not know how to frame. Once the right Scottish service became involved, these situations were often resolved quickly. The real turning point lies earlier, when a person decides whether to ask a simple question at all.

One of the clearest lessons from the project is that most problems newcomers face never begin as legal disputes but they become disputes when early steps are missed. Seen from this angle, Scotland’s legal and administrative systems look strongly preventive. The central task is to help people use the protections that already exist.

This project also showed me that innovation in general begins with an empathetic mindset rather than direct technology implementation. It is essential to listen to the intended beneficiary, precisely identify the unsolved problem, and then innovate to build a solution around it. This course enabled me to implement technology to solve the problem in a simple way.

Finally, the project underlined that design decisions are legal decisions in disguise. Choices about which topics to include, where the tool should stop, and when to hand over to a human all carry consequences for users. Building ScotSpot made those choices visible and reminded me that any future legal technology needs the same care in setting boundaries as in offering help.

(Simplified system flow of the ScotSpot prototype, showing how user questions are routed and answered)

Where this could go next

As a prototype, ScotSpot already points toward practical next steps that could make early guidance more accessible for newcomers. The most immediate development is to widen who can comfortably use the tool. Many newcomers live in Scotland with limited English or prefer another language when dealing with important issues, so multilingual options would allow people to describe their concerns in words that feel natural to them and to receive guidance they can fully understand.

There is scope to refine the existing housing, health and consumer journeys, add more nuanced scenarios and expand into other everyday areas where Scotland already offers strong protections.

For ScotSpot or a similar tool to move beyond a student project, it would also need an institutional home. Someone has to take responsibility for keeping information current, deciding which topics are in scope and managing relationships with organisations such as universities, councils and advice services. Without that governance, even a carefully designed tool will age quickly.

Acknowledgements

This project began in a moment of hesitation. As a Foreign Qualified Lawyer with no technical background, choosing a practical build for my summer project did not feel obvious. In early conversations, Dr. Birgit Schippers, Program Director for the LLM Law, Technology & Innovation, encouraged me to take on the ‘Enhanced Technology Design Project for Law and Legal Applications’. From there, the project developed under the guidance of Professor Wes Oliver, whose habit of listening closely and breaking complex ideas into small, workable steps helped build confidence at each stage of the work.

I am also grateful to the students who trusted me with their stories about everyday worries. Their experiences shaped ScotSpot far more than they realize. Each conversation was a reminder that Scotland already offers a strong, fair legal environment for everyone, and that the real challenge is often helping people understand how to use the protections they already have.

Building ScotSpot has confirmed that some of the most meaningful contributions to ‘access to justice’ involve making existing rights visible, usable and less intimidating at the moments when people need them most.

(ScotSpot is presented here as a supervised academic prototype. The system was fully built and demonstrated as part of the project, but the public version does not currently provide the complete interactive chatbot experience).

ScotSpot Link - ProtoType Landing Page:

https://scotspot-bf5eda.webflow.io/