|

Dr Matt Hannon 2 November 2017 |

Imagine harnessing the power of the ocean’s waves to boil a kettle, light a room or drive an electric vehicle to work. This is a vision the UK has sought to realise as far back as the early 1970s, when it developed a host of exciting new wave energy devices with intriguing names such as Salter’s Duck, Cockerell’s Raft and Russell’s Rectifier.

During the 1980s and 1990s wave energy fell out of favour with UK government, only to re-emerge as a top priority in the UK’s battle against climate change at the turn of the century. Since then almost £200m of public funds have been spent on wave energy innovation in the UK. Even despite this large investment, a commercially viable wave energy technology has yet to emerge.

Our research finds that wave energy’s progress has been hampered by poorly designed government policy and industrial strategy, not least the desire to go ‘too big, too soon’ and commercialise the technology before it was ready. However, a concerted effort to learn from past mistakes, led primarily by Scottish Government, has meant the UK is now better placed than ever before to take wave energy to market. Even so the seismic political forces of Brexit and the Conservative government’s new energy strategy could undo much of this good work and sink it without trace.

To help wave energy weather the storm and accelerate its journey to market our new report identifies 10 key recommendations including:

- Retaining access to EU research & development funding post-Brexit.

- Developing a long-term UK wave energy innovation strategy.

- Improving coordination of energy innovation support within and across governments.

- Avoiding direct competition for subsidies with more established technologies, such as offshore wind and tidal stream.

- Supporting the formation of niche market for wave energy deployment, such as off-grid islands.

Critical weaknesses in policy have slowed wave energy’s progress

These recommendations are based on a 3 year project examining barriers that have undermined wave energy innovation in the UK. In our view the most important barrier was aiming to go ‘too big, too soon’. Funding programmes encouraged array-scale deployment of wave energy before it had chance to prove itself at smaller scales. Consequently, developers over-promised in order to secure funding but then subsequently under-delivered. This eroded investors’ willingness to invest in the technology and triggered the collapse of leading firms (for example, Pelamis) (Figure 1), further undermining the sector’s confidence, legitimacy and growth.

Figure 1: Pelamis P2 device in waters off Aguçadoura, Portugal

Other barriers included a fast changing, complex and poorly coordinated policy landscape that undermined a long-term wave energy strategy and encouraged the duplication of funds. A large proportion of the public budget for wave energy innovation in the UK also went unspent as developers could not meet over-ambitious funding criteria or struggled to secure the necessary match funding from private investors. Wave energy was also ‘crowded out’ by more mature renewable technologies, such as tidal stream and offshore wind.

Finally, a lack of knowledge sharing and collaboration also undermined innovation, stemming from a desire to protect intellectual property and a funding regime that encouraged numerous different developers to individually progress their own device designs in isolation. A lack of test facilities to enable part-scale (e.g. ¼ scale) testing of device prototypes also posed a further barrier to experimentation.

A reboot of wave energy innovation policy

In the early 2010s it became apparent that wave energy wasn’t advancing as quickly as first hoped, following the bankruptcies of market leaders such as Pelamis and Aquamarine Power and the withdrawal from the market of large multi-national companies (for example, E.On, Voith)

Over the past few years significant progress has been made in addressing some of these barriers. Scottish Government’s reaction was to take stock and learn from past mistakes in order to recalibrate wave energy innovation policy, beginning with Scotland’s Wave Energy Summit hosted by then First Minister Alex Salmond in 2014. This learning was translated into action with the establishment of new world-class test infrastructure (for example, FloWave TT) (Figure 2) and knowledge exchange networks (e.g. the Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult).

However, this reconfiguration is best encapsulated by Scottish Government’s Wave Energy Scotland. It encouraged collaboration by funding the common solutions to shared problems, lesson sharing by demanding that any intellectual property was licenced and patient experimentation by avoiding the pressures of private sector investment by offering 100% funding.

Figure 2: FloWave TT wave test tank at the University of Edinburgh (source: Dave Morris)

Seismic political developments threaten wave energy’s future

In light of these changes to the support for wave energy in the UK, it is now much better placed to deliver a commercial wave energy device than it has been in the past. However, this newly configured system is likely to face severe disruption from two wider political developments.

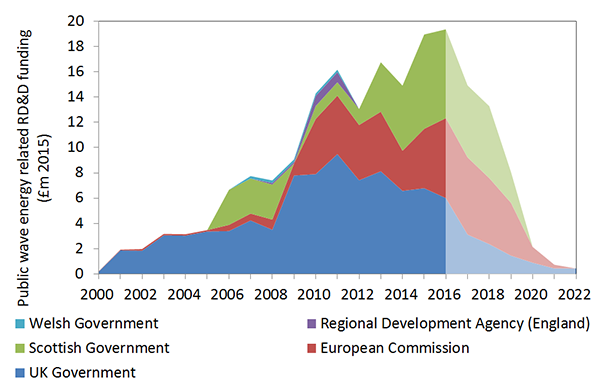

The first is Brexit which threatens the UK’s access to significant EU energy innovation funds. Since 2000, EU funds have accounted for 27% (£53m) of all UK based wave energy-related RD&D and in 2016 EU funding (£6.3m) was greater than that from UK Government (£6m) (Figure 3). Furthermore, failure to access major international EU research funding programmes like Horizon2020 would remove the UK’s primary platform for international collaboration.

If retaining access to these EU programmes is not possible then the UK will have to consider making up this shortfall in funds itself and promoting international collaboration via other platforms, such as Mission Innovation.

Figure 3: UK public RD&D funding for wave energy-related projects by innovation stage since 2000. Full table can be found on page 72 of the full report.

The second is the UK Government’s shift away from investing in radical new technologies like wave energy to driving down costs of more established energy technologies like offshore wind and nuclear, as outlined in their recent Clean Growth Strategy. This trend is already evident (Figure 3) with UK Government steadily reducing its share of funding since 2011. In contrast Scottish Government and European Commission increased their respective shares, both eclipsing UK Government’s spend in 2016.

Together these policy shifts present a very real threat of the Scottish Government finding itself acting alone in developing wave energy technology; undoubtedly one of the most difficult engineering challenges of our time.

Links

- Download the full report here: Hannon, M. J., van Diemen, R., Skea, J. (2017) Examining the effectiveness of support for UK wave energy innovation since 2000. Lost at sea or a new wave of innovation? International Public Policy Institute, University of Strathclyde: Glasgow

- Watch Dr Hannon discuss some of the key findings and recommendations from the research in this short video.

Tags: Brexit News & Blogs