Housing, Health, and What Lived Experience Shows Us that the Evidence-base Misses

Authors: Lisa Garnham, Kat Smith, Ellen Stewart and Clemmie Hill O’Connor

Housing isn’t just a place to live. It is deeply connected to who we are and how we feel. Unsurprisingly, then, housing makes a big difference to our health. While this may sound obvious, understanding how housing shapes health is complicated. As well as the material living conditions that housing provides, we also need to consider how much it costs (and how much money it leaves us for everything else after we’ve paid for it), how stable our housing experiences are and the wider neighbourhoods in which we live. All of these aspects of housing affect health in different ways. They are also shaped by a wide range of policy teams and practitioners across the housing, planning and social security systems, as well as housing markets, construction supply chains and landlords. So, while we know housing matters for health, it can be difficult to pinpoint where to intervene and how to design policies that could meaningfully improve the realities people face.

In our new paper in the diamond open access Journal of Critical Public Health Policy, we explored this challenge by bringing together three different ways of understanding the housing–health relationship: research evidence, policymaker perspectives, and lived experience. We used systems mapping to compare how these different groups conceptualise the housing and health system.

Using systems maps to explore housing as a social determinant of health

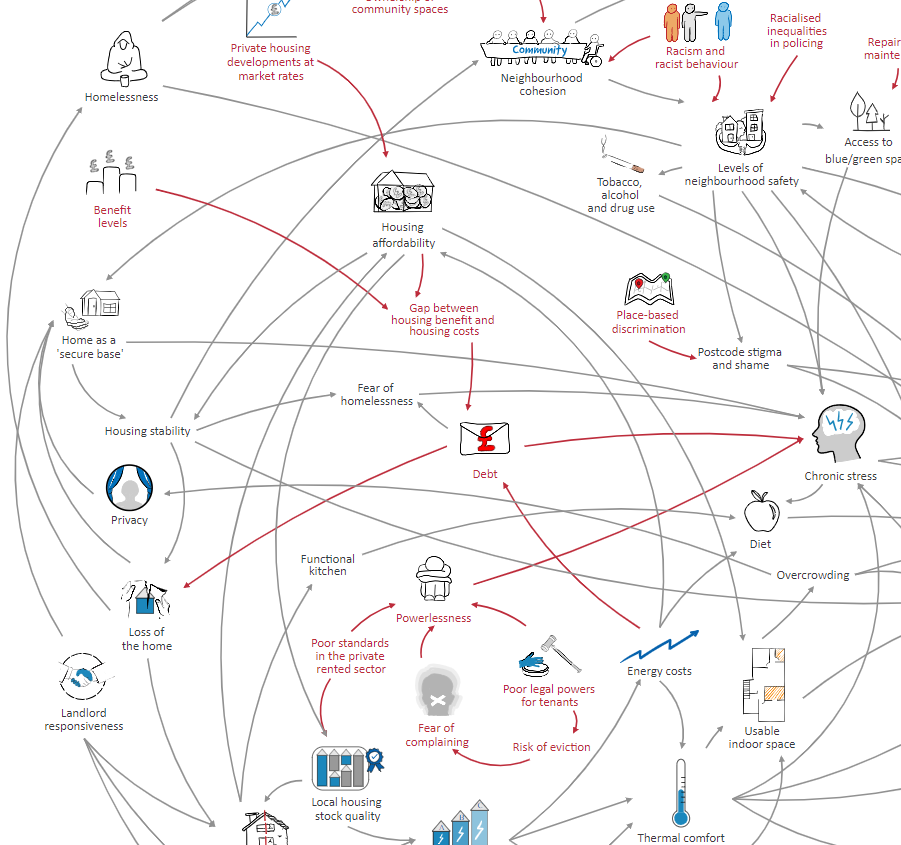

Systems mapping offers a way to visualise complex issues. Rather than isolating single causes or outcomes, maps show multiple interacting factors and feedback loops. For housing and health, this includes affordability, quality, neighbourhood environments, stress, employment, services, and social relationships. All of these factors interact with one another to shape health over time.

To try to unpack some of this complexity, we developed three sets of maps. One map drew on published research evidence on the relationship between housing and health outcomes. Another set was produced with policymakers working on housing-related policy teams in northern England. The third set were co-created with people who had lived experience of the stresses of inequalities. We then compared these maps to explore where perspectives aligned, where they diverged, and what this might mean for how housing policy is informed.

Where and how perspectives aligned and diverged

One of the key insights from the paper is that research evidence and policymaker perspectives aligned closely: both groups draw on formal evidence, reviews, policy frameworks, and shared professional logics about how housing affects health. From an ‘evidence-based policy’ perspective, this seems like good news - it suggests policymakers are drawing on available evidence and that researchers have a good understanding of the policy context. In these policy and evidence generated maps, pathways from housing to health centred on measurable factors like the affordability, quality, and consistency of housing, and the policies designed to affect these factors.

The maps created by people with lived experience, however, made some significant additions to the picture. While they reflected many of the same core elements (affordability, quality, neighbourhood, and consistency), lived experience perspectives highlighted additional issues – notably, the importance of people’s sense of control over their housing situation. For people facing housing insecurity, poor conditions, or unstable tenures, the impact on health isn’t fully captured by the measurable indicators that researchers and policymakers tend to focus on. It is also shaped by the day-to-day experience of coping with stress, uncertainty, navigating complex social security systems, and living with an all-too-common sense that you are being treated unfairly, stigmatised and dismissed. These are not peripheral details: they are central to lived experience accounts of the housing-health relationship.

What We Lose When We Ignore Lived Experience

The stark difference between these three perspectives has profound implications. When policy and research rely primarily on formal evidence cultures (i.e. what is easily measurable, published, and peer-reviewed), important aspects of people’s lives can be missed or underestimated. The stories recounted by people with lived experience of struggling with inequalities reveal links that may not yet be well represented in published evidence, such as the psychological toll of a lack of control, the compounded effects of discrimination, or the mitigating impact of informal support networks.

This isn’t just an academic point. Policies developed without these insights may address affordability or quality in theory, but overlook how people navigate housing problems, so that interventions don’t work as intended. And even when these housing system interventions work (more or less) as intended, they may not have the impacts we would expect to see on health, since we don’t have a full appreciation of all of the different ways that housing impacts on health outcomes.

Decentring dominant evidence cultures

One of the challenges we highlight is the way dominant ‘evidence cultures’ in public health and UK policy prioritise knowledge arising from quantitative data that is already being regularly collected. While rigorous evidence is essential, privileging what we already measure to the exclusion of lived experience can narrow our understanding of complex social problems.

Decentring these cultures doesn’t mean abandoning quantitative evidence; it means expanding what counts as valid, useful knowledge. This could include narratives, participatory mappings, and other forms of experiential insight that reveal the emotional, relational, and contextual factors that shape housing and health. Crucially, it means ensuring that policies are designed and evaluated in ways that reflect people’s lived experiences, as well as quantifiable indicators.

Lessons for Policy and Practice

So what can policymakers, researchers, and advocates take from this work?

- Evidence cultures need broadening, so that policy decisions are informed not only by what is measurable, but also by what matters deeply to people’s lives. Without this, policymakers and researchers can miss important pathways linking social determinants, such as housing, to health outcomes.

- Systems mapping is more than a technical tool - it can be a way to bring different perspectives into dialogue and reveal blind spots. To try to help with this, we followed up the work in this paper by developing a protype of a new kind of systems mapping software, which layers lived experiences on top of more traditional evidence about housing and health.

We welcome feedback on the paper and the layered map of housing-health (please email Lisa.Garnham@strath.ac.uk).

Funding and acknowledgements:

We are grateful to everyone who contributed to the creation of the maps described in this blog. This work was supported by the UK Prevention Research Partnership (MR/S037578/2), which is funded by the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Health and Social Care Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, Natural Environment Research Council, Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), The Health Foundation and Wellcome.