Promoting Cultural Awareness Through an L3 Experience: Pushing at the Boundaries?

In this blog entry, David Roxburgh (a Senior Teaching Fellow in the School of Education) reflects on themes arising from his recently completed doctoral thesis, ‘An Analysis of the Promotion of Chinese Culture within an L3 Language Experience in Selected Scottish Primary Schools’.

Overview of my wider research theme

My work in Chinese language and culture (CLC) stemmed firstly from my interests developed during my previous teaching career in primary schools and then through the various international/ China facing roles that I have held at Strathclyde University. My study investigated the promotion of Chinese culture in selected Scottish primary schools through a third language (L3) experience, which I link to policy below. Three research questions aimed to give distinctive insights into current classroom practices, stakeholders’ cultural views and the programme’s impact on pupils’ understanding of the country and its people:

- Within the selected schools, what type of L3 Chinese cultural programme has been experienced by pupils at the Primary 5-7 stages?

- What similarities/ differences exist in how a ‘Chinese cultural programme’ is construed by those Scottish teachers and visiting Hanban teachers* involved in the study?

- How has an L3 cultural programme shaped the knowledge and attitudes of pupils at Primary 5-7 towards China, Chinese people and Chinese culture?

* Teachers/ graduates from China sponsored by the Hanban Organisation to spend up to 2 years in Scotland promoting CLC in schools.

Given the lack of specific Scottish research in this area, I deliberately adopted a layered approach to these questions so that each connected to, and contributed towards, the others, which my viva examiners recognised as the means by which both breadth and depth were achieved. I adopted a mixed methods approach to gain wider and very specific perspectives. Quantitative research was carried out through an on-line survey of 374 pupils across primaries 5-7 in five schools within three Scottish local authority areas with analysis through the use of SPSS software to present ‘big picture’ data across the sample as a whole. Given the nature of quantitative data, the picture painted of classroom practices and pupils’ attitudes was purely illustrative and required complementing through qualitative approaches aiming to explore and understand issues in more depth. For this purpose, focus group interviews took place with 4 distinctive sets of participants over the course of a 14-month period: 16 Scottish primary and 11 Hanban teachers, 3 Professional Development Officers working at Strathclyde’s Confucius Institute supporting CLC activities in schools and, finally and very importantly, 140 pupils across primaries 5-7. This included pupils prior to their L3 involvement to get a sense of the benchmark of any existing knowledge and understanding of CLC. Each of these groups presented ethical dimensions, which I explore fully in my methodology chapter and may be of interest to some of the readers of this blog.

Policy context

Though my research considered UK and international perspectives in the literature review, it was the Scottish context that formed the foundation for the study. ‘Language Learning in Scotland: A 1+2 Approach’ (Scottish Government, 2012) is effectively the current driver of national policy and was intended for full implementation in all schools by August 2021, though the ongoing impact of the Covid pandemic has complicated this goal. There is a commitment to give every child an entitlement to learn two languages in addition to English: the first from primary one (age 5) through to the end of the ‘Broad General Phase (BGP)’ of Scottish education (ages 14-15), and a second introduced from no later than primary 5 (age 9-10). In marked contrast to the second language, which must be provisioned for from Primary 1- Secondary 3, the choice of the third offers maximum flexibility as there is to be no hierarchy, thus offering opportunities to broaden pupils’ experiences of non-traditional languages. This is where most schools teaching Chinese (Mandarin) begin. The 1+2 document makes specific reference to the notion of an ‘inverse methodology’ in the context of CLC, where it is hoped that a very strong focus on cultural inputs acts as a key driver for the complementary study of the language. As the title of this blog suggests, this could be a means of pushing at the boundaries of promoting culture through language learning, or indeed act as a means of reinforcing these in unhelpful ways that introduce stereotypes into pupils’ minds at an impressionable age. Though my wider thesis covers a lot of ground, I briefly consider one specific aspect of cultural awareness in the next few sections.

Cultural promotion: tensions between large and small culture(s)

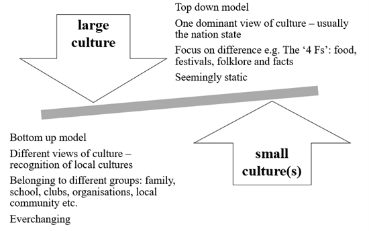

In exploring the literature base, collecting and analysing data, one of the themes that formed was the tensions round the promotion of culture. In my research, this was framed round notions of ‘large culture’ and ‘small culture(s)’ and is represented in the diagram below:

Figure 1: Researcher’s summary of large and small culture(s) taken from the work of Holliday and Kramsch

In selected works, Holliday (1999, 2018) introduces notions of ‘large and small cultures’ in ways that are also similarly referenced by Kramsch (2009a). Holliday believes that large cultures are about the emphasis on difference and detail with regards to the norm for any particular ethnic, national culture or group. However, small culture is less prescriptive and finds softer boundaries, which may or may not have ethnic, national or international characteristics and are more engaged with social processes that continually evolve. Small culture is not dependent on ethnicity and nation and is to be found more at the heart of day-to-day life and contexts, for example, family, friends, places of work, leisure etc. However, the term small is not just related to the social grouping, but how social interaction takes place and does not try to essentialise what results from this.

Kramsch (1998, 2009a, 2009b) links to this in discussions of ‘big C’ culture which stress notions of learning about a country through its history, geography and the Arts in ways that promote a stable narrative about its culture from its roots into the present and into the future. This can be based on a set of moral values to which others may or may not be able to relate and which often places such cultural dimensions at the prestigious end in the minds of some levels of society. She also highlights its ‘small c’ side and the tendency to dwell on native speakers’ ways of ‘behaving, eating, talking, dwelling, their customs, their beliefs and values’ (2009, p. 222) in order to think and experience culture like speakers of the language. This tendency can neglect the wide variation that exists in groups, communities and nations across any context where the focus becomes that of promoting typical or stereotypical behaviours of the dominant group or native speaker group that will make sense of the exotic in the eyes of any learner or outsider to the culture in question.

Discussions of the forming and impact of exposure to large and small cultures were of particular importance to my thesis given the tensions that arise from each perspective and the messages these send out to those engaged in trying to promote cultural understanding and the recipients of such work, which in my context were pupils at the P5-7 stages in Scottish schools at the very formative beginnings of their CLC experiences.

Some selected findings

Analysis of the very large amounts of data that I gathered daunted me at times, but adopting the thematic approach promoted by Braun and Clark (2006, 2013) and their six steps helped give clarity to the process involved, particularly notions of what constituted a theme and the iterative process that happens in reaching these. The 3 discussion chapters in my thesis stayed true to this in that these presented themes more widely before returning back to the research questions in the final chapter, which I draw upon selectively below.

My data highlighted a very strong focus on presenting China, its people and culture from what I referred to earlier as ‘large/ national’ perspectives with a focus on tradition through activities reinforcing Kramsch’s (1998, 2009a, 2009b) ‘4 Fs’: food, festivals, folklore and facts. This created a very uniform view of Chinese people and culture with much less engagement in aspects of small/ local cultures to which pupils may be better able to relate. The data showed that across P5-7 as a whole, there was clear repetition in pupils’ learning with a need for better progression in their experiences and understanding. Though there were certainly examples of interesting application and contextualised learning across the curriculum taking place, this was in the minority and something that needed sharing more widely to show the potential of CLC as a balance to the promotion of traditional culture. Broad indications for its language element existed within the updated framework for L3 practices from Education Scotland (2019), however there seemed to be no specific national guidance and little at local/ school level on the equivalent cultural base. As a result, this was most often left to the Hanban teachers’ own judgments around what would best constitute Chinese culture. This was recognised by this group as being very open to individual interpretation and, as a result, could encourage a fall back to some strong cultural messages from organisations such as Hanban given in pre-departure training, which were recognised as not always suitable for local contexts. The work of PDOs from the associated Confucius Institute tried to promote balance and other perspectives. However, these messages were hampered by structural issues such as lesson duration, perceived lack of resources and general expectations around the dual delivery of language and culture within lessons, which some teachers felt prioritised the former over the latter.

Recommendations

This research theme gave rise to some particular recommendations that I reflected upon more fully in the final chapter of my thesis and included the need for:

- a better balance in the representations of modern/ traditional China;

- clearer advice to Scottish and Hanban teachers on making ‘culture’ accessible to primary aged pupils;

- better progression in cultural themes across CLC experiences at the P5-7 stages to avoid high levels of repetition of learning, whilst still recognising the need to build on previous content; and

- fuller engagement with additional people, organisations and sources that could represent China and Chinese culture more widely.

Follow ups arising from the research

I passed my viva with minor corrections, which were completed and accepted in September 2021. Since then, I have been looking for various avenues to promote my work and its findings, rather than just see this as the end of the journey. I have made further contact with the Confucius Institute for Scotland’s Schools to discuss my work and support the professional development of the next round of Chinese exchange teachers, which I feel is particularly significant given their distinctive roles in the promotion of CLC. Means by which I can engage other practising teachers beyond this are also important, and I have been giving inputs on the cultural dimension to language learning and social studies in the primary school to PGDE/ undergraduate student groups at Strathclyde. Also, reconnecting with those Scottish teachers involved in my research, now that the pandemic situation has become more settled, and schools look to re-engage the rest of the wider curriculum beyond the core areas is key. Finally, I continue to work with my second supervisor, Ms Joanna McPake, and others to consider how the lessons from this work might influence third language practices more generally beyond the specifics of CLC and have some conferences planned early in the new academic year to explore such ideas. These sorts of activities are important in trying to create, and maintain, momentum from what was a really extended research period from which I grew immensely in personal, academic and professional ways that certainly pushed me out of my boundaries.

I am always happy to discuss my research with those interested and can be contacted by email (david.roxburgh@strath.ac.uk).

The thesis is also available in full online through SUPrimo.

Selected references

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage

Education Scotland. (2019). Language Learning in Scotland: A 1+2 Approach, Guidance on L3 within the 1+2 policy (updated May 2019).

Holliday, A. (1999). Small cultures. Applied linguistics, 20(2), 237-264.

Holliday, A. (2018). Understanding intercultural communication: Negotiating a ‘Grammar of Culture.’

Kramsch, C. (1998). Language and culture. Oxford University Press

Kramsch, C. (2009a). The multilingual subject. Oxford University Press.

Kramsch, C. (2009b). Cultural perspectives on language learning and teaching. In K. Knapp & B. Seidlhofer (Eds.), Handbook of Foreign Language Communication and Learning (pp. 219-246). De Gruyter Mouton.

Scottish Government. (2012). Language Learning in Scotland: A 1+2 Approach.

Published 10/08/2022

Image - www.epictop10.com