Plasma mirrors capable of withstanding the intensity of powerful lasers are being designed through an emerging machine learning framework.

Researchers in Physics and Computer Science at the University of Strathclyde have pooled their knowledge of lasers and artificial intelligence to produce a technology that can dramatically reduce the time it takes to design advanced optical components for lasers - and could pave the way for new discoveries in science.

High-power lasers can be used to develop tools for healthcare, manufacturing and nuclear fusion. However, these are becoming large and expensive owing to the size of their optical components, which is currently necessary to keep the laser beam intensity low enough not to damage them. As the peak power of lasers increases, the diameters of mirrors and other optical components will need to rise from approximately one metre to more than 10 metres. These would weigh several tonnes, making them difficult and expensive to manufacture.

Accelerated process

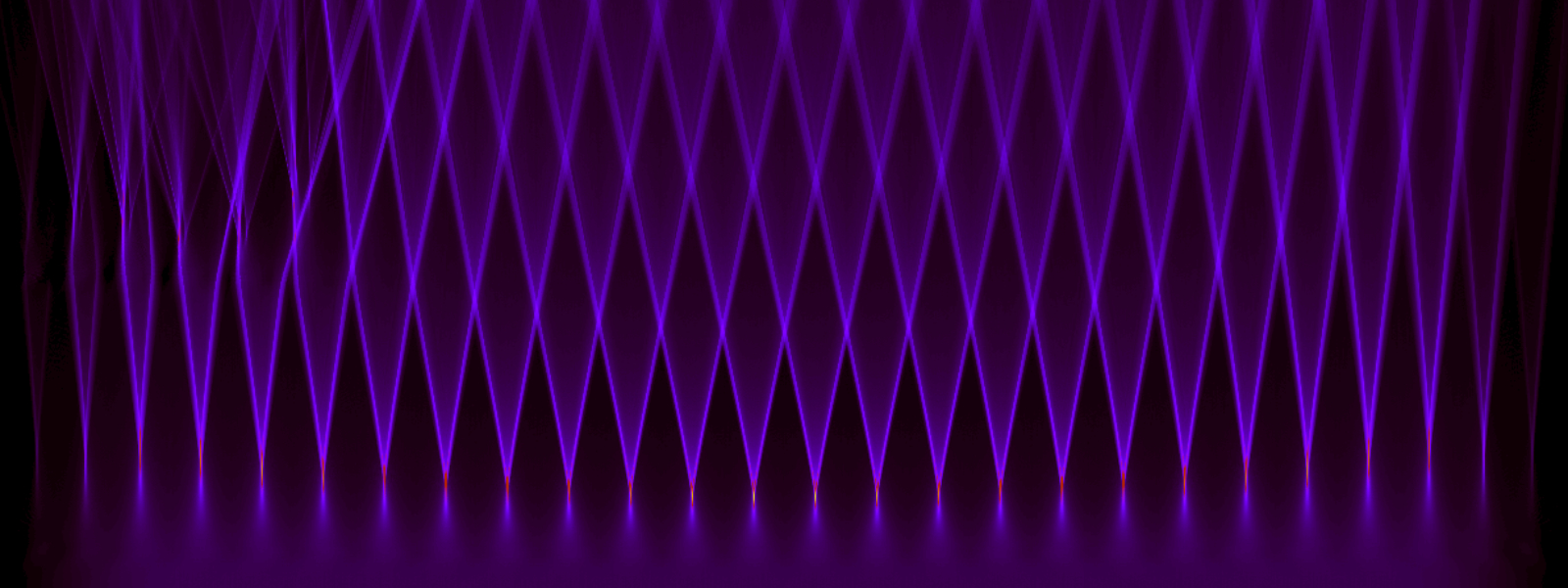

The researchers have explored an alternative use of plasma – ionised gas that makes up more than 99.9% of the visible universe - which is highly resistant to damage. This could reduce the size of the mirrors to millimetres, but the challenge has been designing plasma structures that reflect light efficiently and reliably. The researchers have accelerated the design process by coupling machine learning algorithms with computer models.

The research has been published in Nature Communications Physics.

Slav Ivanov, of Strathclyde’s Department of Computer and Information Sciences, the study’s lead author, said:

A traditional design approach develops many prototypes that are tested on each cycle to eventually realise the objectives. This usually involves numerous iterations, and the complete design process can involve hundreds of thousands to millions of iterations. Machine learning shortens it to just a few dozen or so iterations before an optimum design is found.

Professor Dino Jaroszynski, of Strathclyde’s Department of Physics, who led the study, said: “This research can also be an engine of discovery. By specifying a particular objective, only limited by our imagination, the mirror can compress a pulse; this was wholly unexpected. By investigating why the pulse compresses, we discovered it is due to a time boundary. The plasma layers deform like a concertina, which adds new frequencies to the reflected pulse and delays different parts of it, leading to compression.

“This has far-reaching implications. We can tailor a design to meet our objectives and potentially discover new mechanisms.”